Now there are two brick features in the L-shaped cellar near James Fort’s first well.

Were these brick features in Structure 191 heating sources for metallurgical testing or for cooking—or something else? The investigation of these two features is informed by the 2007 discovery of two similarly-constructed bread ovens in a blacksmithshop/bakery cellar (Structure 183) near the north bulwark of the fort.

The cellar being explored now is 25 feet long and dates to the early James Fort period (1607-1610). It is in an area just west of the brick church tower and just north of the 1608 church. This cellar aligns with James Fort’s first well, which sits 10 feet away to the west and at the same angle.

Archaeologists began to explore one brick feature at the end of this cellar in mid-July. The brick stack measures about three feet and features noticeably precise mortaring that was not a feature of the ovens in Structure 183. Then in August the Jamestown Rediscovery Project staff found another brick feature about 10 feet away, in the middle of the southern “foot” of the L-shaped cellar. This second feature’s bricks cascade down into a jumbled pile, showing a collapse of the structure the bricks had formed.

Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologist Danny Schmidt said these two brick features may be from an earlier time than the baking ovens found in 2007, which are believed to have been constructed ca. 1610-11.

Two clues to the ca. 1608-10 date for the L-shaped Structure 191’s ovens: its fill dates from the June 1610 cleanup of James Fort, ordered by the newly-arrived Lord Governor and Captain General of Virginia, Lord De La Warr. And colony President Edward Maria Wingfield wrote that in early 1608 “Captain Newport . . . employed some of [his men] about a fair storehouse others about a stove.”

Could one of the brick stacks be the “stove”? Today we associate a stove with cooking food, but in the early 17th century it could also refer to a sweating room for health treatments, a chamber heated with a furnace, or a heating apparatus itself.

The two brick features now being examined may be for food preparation—equipment in a common “kitchen” for the occupants of the fort in its earliest days, said Dr. William M. Kelso, head of archaeological research at Historic Jamestowne. He noted that a lot of sturgeon bones have been found mixed with the ash in front of the ovens.

Schmidt cautioned, “We can’t be certain yet if the ash is from the building possibly burning down or ash coming from the brick features. If it is ash from the brick features, that ash would be an occupation layer, during the use of the cellar.”

Ash was an important clue in the excavations of the blacksmith shop/bakery cellar Structure 183. There was a clear ash delta from one of its ovens, indicating that oven was in use longer than the other one. That and repairs made to the threshold of the oven indicate it could have been in use until 1617, when the cellar was backfilled and another structure was built over it.

The circular shape of the flue on the southern end of the L-shaped cellar also looks very similar to the flue plan on the ovens excavated in 2007—but the one on the east end of the L-shaped cellar has a trapezoid shape.

The bread ovens had brick façades to the turtle-shaped oven spaces that had been dug out of the clay soil. Further excavations in the L-shaped cellar will show if its two brick features were built the same way.

The L-shaped Structure 191 will be the focus of the archaeological work this fall; Kelso said only a third of it has been examined so far. He added that the many artifacts found in the L-shaped cellar so far are not necessarily informative about the use of the structure because they date from the time when it was backfilled as part of the fort cleanup and not from when the cellar was in use.

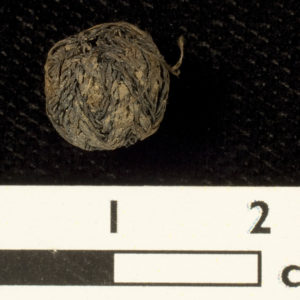

In August that fill has yielded enough sherds to mend two more Indian pots together; an ivory finger ring; the iron heads to a hammer and a pike; a bone handle to a knife; and scores of glass, shell, lapidary, and bone beads. One fiber-wrapped bone bead is a rare survival in a dry context. The round bone bead, which may have been used as a doublet button, is completely covered by the twisted and woven fiber.

related images

- Bone

- East brick feature in Structure 191

- Fiber-wrapped bone bead found in Structure 191

- Mended Native American Pottery from James Fort Excavations

- Part of an ivory ring found in Structure 191

- Structure 183’s bread ovens excavated in 2007

- West brick feature in Structure 191