In May, Jamestown Rediscovery added five new archaeologists to the team who will be working through the summer. New staff members include Chardé Reid and former field school students and interns Kaitlyn Fitzgerald, Jack Beimler, Anna Shackleford, and Katie Dowling. Reid, Beimler, and Dowling are working at the Angela Site, while Fitzgerald and Shackleford are excavating in the Memorial Church. All are eager to participate in the excavations at Jamestown.

Archaeologists continued to make exciting new discoveries at the Angela Site. They recovered a small, cast iron cannonball or falconet from the top layer of large clay, loam-filled pit feature in the south portion of two new units. They also uncovered several ceramic sherds dating to Angela’s occupation of the Captain William Pierce site, including an earthenware drinking cup made at Jamestown, an English delftware drug jar, a Westerwald drinking jug, and a Surrey-Hampshire Border ware cooking vessel. Another notable find is the product of a pipe maker in England’s West Country: a white clay pipe stem with a gauntlet impressed on its heel. According to Curator of Collections, Merry Outlaw, all of the finds have parallels to material culture from ca. 1620-1645 sites throughout the James River Basin.

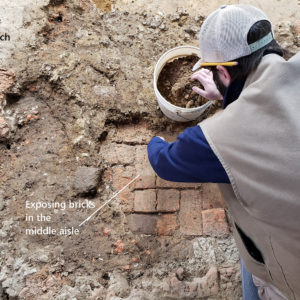

In May, the Church team examined a mysterious clay-filled pit located in the middle aisle that spanned the choir and the body of the church. Uncertain if the pit was a test excavated during the early 20th-century excavations, or if someone robbed bricks here in the colonial period, archaeologists decided to investigate. Last fall, the team removed a section of the early 19th-century churchyard wall that cut through the eastern third of the church. While deconstructing the wall, they discovered that it cut into, thus postdated the clay pit. They also exposed the profile of the middle aisle, revealing the depth of the pit and that it sealed intact, undisturbed brickwork. This was quite a welcome surprise! The top few inches of a burial in the aisle, into which the surviving brickwork had settled, was also visible.

“Once Bob Chartrand excavated the clay, we learned that its purpose was to fill the hole created when this brick slumped into a burial below,” explained Field Supervisor Mary Anna Hartley. “Since we have outlined numerous burials across the entire church floor, discovering a burial beneath the aisle was not unexpected. The real surprise was that the burial was not robbed or previously tested by past excavators.”

Almost certainly, this surviving brickwork slumped into the burial after the abandonment of the church in 1750 because the parishioners of an active church likely would have releveled and laid a new floor. Current excavations revealed that the brickwork was laid in a herringbone arrangement, a zigzag pattern resembling the bones of a herring. Fortuitously, after the brickwork slumped, the depression was infilled. This occurred prior to the construction of the churchyard wall because, if exposed, the bricks would have been used in the wall, and the pattern would have been lost to history!

related images

- Archaeologists added to the Rediscovery team for the summer: Chardé Reid, Katie Dowling, Kaitlyn Fitzgerald, and Jack Beimler

- Archaeologists Chardé Reid and Katie Dowling remove the overburden in a test unit at the Angela Site

- Chardé Reid cleans a test unit at the Angela Site

- The excavated church aisle and clay pit

- Archaeologists map the clay pit in the middle aisle in April 2018

- Archaeologists Dave Givens and Mike Clem (of DHR) dismantle the 19th-century churchyard wall that cut through the east end of the church (Fall 2017)

- Angie Tomasura removes bricks from the 19th-century churchyard wall (Fall 2017)

- Burial and surrounding features

- Bob Chartrand exposes the intact brickwork sealed by the clay-filled pit in the middle aisle of the church

- Bob Chartrand exposes the intact brickwork in the middle aisle of the church

- Bob Chartrand exposes bricks in the middle aisle

- Brickwork and burial in the church floor

- Brickwork in the middle aisle