The 2024 field school is fast approaching and the team is readying their plans for the students’ arrival. The students will be excavating in four main areas, just in front of the Archaearium museum, in Smithfield, adjacent to the Godspeed Cottage, and in Governor Argall’s addition near James Fort’s north bulwark. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) indicates there is a possible building just in front of the Archaearium museum (on the south side). The museum was built on Statehouse Ridge, high ground where the 17th-century statehouse was situated. Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford will lead the students’ excavations here, opening seven ten foot squares in a line with ten feet separating each one, roughly parallel to the Archaearium’s south facade. The goal here is to put human eyes on what exactly the GPR is “seeing” but also to more generally do some exploratory excavations in this area, keeping an eye open for statehouse rubble and graves. Past excavations just to the north and west have discovered dozens of individuals buried in the area.

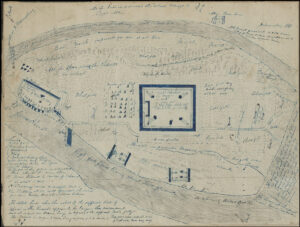

On the other side of the open field, about a hundred yards to the southeast, Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo will be leading another team of field school students in excavations where GPR indicates the presence of three 6-foot by 6-foot buildings. These may correspond with buildings represented in a Civil War-era map owned by William & Mary that is housed at their Special Collections Research Center at Swem Library. Although the map is of an inaccurate scale, it indicates several heretofore unknown structures. Possible uses for the structures found by GPR include soldier barracks or shelters for contraband (slaves that escaped into Union-held territory). Union soldiers held Jamestown Island for the majority of the war and it served as a mecca for enslaved persons wishing to escape their bondage, even if it meant swimming over a mile across the James from Surry County to the south. Nearby, Director of Archaeology David Givens will examine a large, deep feature identified via GPR. This feature looks very similar to the 1608 military trench found to the east, and may be a continuation or related outwork. Whatever it is, the GPR suggests this feature will be a substantial find.

The field school students will be exploring a third excavation area to the northeast adjacent to the Godspeed Cottage. This was Robert Beverley’s property, prominent clerk, burgess, and author of The History and Present State of Virginia (1705). A GPR survey here indicates the presence of a large, possibly metal object, as well as a number of possible graves. These excavations will be close to the encroaching Pitch and Tar Swamp and the condition of the archaeological resources here should be informative as the team pivots to address those areas of the island that are closest to the rising waters. No excavations have been conducted in this area, and the goals here include investigating the GPR findings, finding features related to the Beverley property, and observing the effect of the nearby swamp on the features as a whole.

The fourth area of excavation during field school, led by Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, will be located just to the northwest of Governor Argall’s addition that was built in the late 1610s during his deputy governorship. The building was appended to the northernmost row house that was just inside and which ran parallel to the fort’s western palisade wall. There are some indications that the addition may have extended to the northwest, meaning at least a portion of the fort’s original western palisade wall was down during the addition’s construction between 1617 and 1619. A GPR survey was conducted in this area in January but the results were inconclusive and so the archaeologists will bring shovels and trowels to expose what the radar could not. Several feet of the earthworks from Confederate Fort Pocahontas lay on top of the 17th-century layers which, along with multiple nearby trees’ roots likely helped obscure the target from the radar.

Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technicians Hannah Barch, Josh Barber, and Ren Willis are carefully scraping away at the layers of a military ditch, part of the “flag” feature on the Zuñiga map of 1608. As was the case with the section of the ditch south of the modern footpath, there was a thick clay cap covering the earliest layers. This same cap has been found on a number of features across the site and is thought to be part of Lord de la Warr’s order that the fort be cleansed after his arrival in the spring of 1610. The colony had just experienced the Starving Time winter of 1609/1610, a desperate time in which the majority of the settlers perished and many of the fort’s structures had fallen into disrepair. A narrow channel is present at the base of the ditch, just like the team saw in their earlier excavation to the south. This was probably a water channel so that the soldiers manning the ditch would not be trudging through mud and water. Natalie, Hannah, Josh, and Ren will continue excavating the ditch as it progresses to the north. Very few artifacts have been found here so far, which is not unusual for such an early feature, especially given its short period of use before being filled in.

At the clay borrow pit, Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, and Archaeological Field Technicians Josh Barber and Hannah Barch have hit subsoil in a number of places, meaning the bottom of the pit has been reached in those spots. Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo posed an ice cream metaphor for the uneven bottom of the pit. When you scoop ice cream, you don’t scoop the same spot each time, you take some from all different parts of the container. That is a good visual for the borrow pit’s uneven bottom, and Anna and the team are tackling the excavations there as quickly as they can because it rarely dries out long enough (especially on the northern side facing the swamp) to get any work done. Because of the tidal nature of the James River in this area, a storm in the Atlantic, even when it brings no precipitation to the island, can bring flooding via the river-fed swamp because of the tidal surge it creates. The archaeological team pays close attention to the river level predictions as a result and looks for openings in which to move forward. Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown is excavating a zig-zag ditch that runs through the borrow pit area, its shape deriving from the fact that it accompanied a split-rail fence. The ditch dates to 1652 or later as indicated by wine bottle glass found inside it, that type of bottle not being in use prior to that year. What the ditch delineated is not certain at this point. It could have served as a boundary between two properties or as a fence for the Great Road which traversed the island just a few feet to the west.

Visitors can now experience the new and improved 1680s Church Tower. The glass roof, glass portal to the 1617 church foundations, new floor, and new signage are all complete. The sunlight coming through the roof makes the whole interior bright and airy, enabling easy viewing of the 1617 church foundations underneath its glass portal and the new signage explaining all there is to see. The roof and glass portal were a collaborative effort between Director of Conservation and Collections Michael Lavin, Stemann Pease Architecture, Daniel & Company Contractors, and the archaeological team. Michael served as the project manager, coordinating all the moving pieces and making sure deadlines were met. The archaeologists conducted a thorough excavation of the Church Tower floor, exploring the Tower’s builder’s trench and finding a section of the fort’s 1607 palisade wall in the process. They also conducted final excavations and cleaning of the 1617 church foundations prior to the glass portal installation. Archaeologist and Director of the Voorhees Archaearium Museum Jamie May designed the signs that explain the history of the Tower through the archaeological excavations, detailing the features and artifacts found beneath the visitors’ feet.

The blacksmith shop is in the midst of a major renovation that includes a new roof and mud and stud walls. Built on the spot where James Fort’s blacksmith shop was found by archaeologists in 2006, the shop has the same dimensions and its main wooden structural posts the same orientation as the one built in 1607. The renovations are part of a focus by the historic trades team to make the shop an industrial hub for the fort. The historic trades team of Willie Balderson, blacksmiths Shel Browder and Steve Mankowski, and carpenters Danny Whitten and Jesse Robertson have been replacing rotted rafters and installing a “bark” roof made of polyurethane. William Strachey, secretary of the colony wrote that the colonists “found [a] way to cover their houses: now (as the Indians) with barks of Trees, as durable, and as good proof against storms, and winter weather.”1

The team is making several changes to the wood prior to installing the new rafters. This includes removing the bark to help prevent insect infestations. Insects lay eggs under bark and the resultant larvae in turn eat portions of the wood. The wood is also treated with a copper azole solution that helps keep insects, mold, and fungus at bay, all of which contribute to wood’s deterioration. All of the carpentry was done with traditional tools, and one of the goals of the blacksmith shop is to be able to build and mend these tools, reproducing those found by the archaeologists in features all across the site. This has brought the historic trades team indoors, into the collections Vault where the curators and conservators assembled many of the iron artifacts for the blacksmiths to study. With these artifacts as their guides, using traditional methods and on the spot where some of the original tools were likely made, the blacksmiths will make fully functional tools that will help build and repair the reconstructed structures inside the fort.

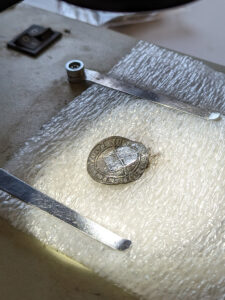

In the lab, Senior Conservator Dan Gamble has been treating some of the silver objects on display in the Archaearium. Over time silver objects become tarnished through reactions with oxygen and sulfur in the air. Though the Archaearium’s temperature and humidity are monitored and regulated and the cases sealed, some reactions still occur over time. Dan spends hours on each piece, using a scalpel and a microscope to slowly and carefully remove the tarnish buildup. Some of the highlights of the pieces Dan conserved this month include a 1582 English Sixpence bearing the likeness of Elizabeth I, a Livonian schilling minted in Riga made of billon, and a silver ear picker. His retreatment of the 15th-century breastplate is almost complete at which point it will go back into the Archaearium.

Associate Curator Janene Johnston is working on Jamestown’s collection of spangles for the reference collection. Similar to today’s sequins, spangles were used to embroider clothes and other textiles to catch light and draw attention to the wearer or decorated item. There are 29 spangles in the collection aside from the captain’s sash which contains dozens of the teardrop-shaped variety. There are three types of spangles in the collection, a round silver gilded type, a teardrop-shaped silver type, and a round copper alloy type coated in silver. Janene conducted portable X-ray Fluorescence analysis of each spangle to determine their elemental composition. This non-destructive process sends photons into the spangle causing the elements comprising it to fluoresce, sending X-rays back into the sensor. Each element has characteristic energies (frequencies) allowing for the identification of the elemental composition of each spangle. Be on the lookout for the spangle artifact webpage, coming soon!

Senior Curator Merry Outlaw is working on a monograph with Dr. Eric Lapp on the collection’s Roman oil lamp entitled “The Roman Oil Lamp from Jamestown: A Biography.” Dr. Lapp is a lychnologist (an archaeologist who specializes in the study of lighting methods from antiquity to the early modern period) and the book focuses on the lamp, dating to the 2nd century CE. It was probably buried with a Roman soldier and was to light the way as he entered the afterlife. The lamp was unearthed and probably purchased to serve as a curiosity in a gentleman’s cabinet of curiosities, a popular way during the 17th century to demonstrate one’s worldliness. The lamp was probably owned by one such gentleman who brought it with him on his voyage to the New World. The book will be geared towards children and young adults and will be STEM(Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math)-heavy.

The archaeology team excavated a full course (the 9th from the top) of the Governor’s Well bricks for conservation and curation. Plastic tape was wrapped around each brick and then numbered so that its exact spot in the course can be recalled. It should be mentioned that this was the ninth course from the top of the well that survived. Much of the top portion of the well was destroyed during the construction of Fort Pocahontas in 1861. The bricks will now be cleaned, given a unique artifact number, and cataloged in Jamestown’s database.

Associate Curator Emma Derry attended the Society for American Archaeology annual meeting in New Orleans this month. Highlights included a session on burial archaeology at Colonial Williamsburg, featuring Dr. William Blakey from William & Mary and Dr. Raquel Fleskes from Dartmouth, a research partner of Jamestown studying ancient DNA. Emma also attended several sessions on curation, including “Storeroom Taphonomies: Site Formation in the Archaeological Archive” which focused on the effects post-excavation environments and interventions have on artifact assemblages and featured a presentation by Magen Hodapp, who’ll be joining Jamestown Rediscovery as our new zooarchaeologist in May. The conference also provided an opportunity for Emma to catch up with former Jamestown intern Lauren McDonald who now works at Colonial Williamsburg and former Jamestown zooarchaeologist Alexis Ohman who now works as an archaeologist for the Navy within their Cultural and Natural Resources division.

Coffin nails and Spanish olive jars have taken the majority of Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens’ time in April. Lauren is gathering coffin nails and making sure they’re properly cataloged prior to x-raying by Conservator Don Warmke. She has also spent many hours working with our new curatorial intern Amanda Nedell looking for mends of Spanish coarseware olive jars. Before these “puzzle pieces” can be searched for possible mends, the sherds were retrieved from long-term storage and inventoried or cataloged. Amanda then labeled each piece with its context number. After Lauren entered each of these artifacts in the database, the process of looking for mendable pieces begins. Clues while looking for pieces of the same vessel include color, thickness, turning patterns, interior glaze similarities and burning characteristics.

The curatorial team is working with the archaeologists to identify and catalog architectural artifacts from the Church Tower excavations. Quartzite, granite, mortar, and coral are among the types of materials that are currently being processed. The archaeologists’ knowledge of the excavations — both recent and throughout the history of the project — will be crucial as the team attributes each of the materials to the four different churches all built on roughly the same spot.

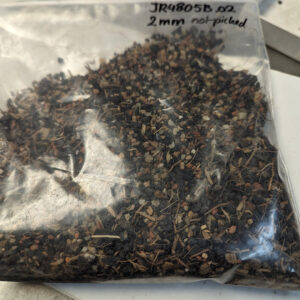

A team of volunteers and interns are picking through the small materials found in the builder’s trench of the Governor’s Well. This conglomerate of rocks, small twigs, and artifacts is the result of water screening the soil excavated from the trench. The task takes patience and a keen eye. Some of the artifacts found this month include nut shells, lead shot, seeds, and native ceramics.

Conservator Don Warmke has completed his conservation of one of the partial swords excavated from the Governor’s Well. It is now being housed in the Vault’s dry room, where temperature and humidity are tightly regulated and monitored to ensure future corrosion is kept to a minimum. Senior Conservator Dan Gamble has almost completed his conservation of another partial sword found in the Governor’s Well. It is also being kept in the dry room in between his conservation treatments. You can read more about the discovery and conservation of these swords in past dig updates.

1 William Strachey, A True Reportory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, upon and from the Islands of the Bermudas: His Coming to Virginia and the Estate of that Colony Then and After, under the Government of the Lord La Warr, 1610.

related images

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid excavates a portion of the 1608 ditch.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch removes the upper layers of a section of the 1608 ditch.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis water screen the soil excavated from the 1608 ditch.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis discusses the latest excavations with visitors.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas uses her trowel to gently scrape away soil in the clay borrow pit excavations.

- Archaeologists Sean Romo, Gabriel Brown, and Mary Anna Hartley discuss the excavations of the zig-zag ditch near the clay borrow pit.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas at work in the clay borrow pit excavations.

- Excavations at the clay borrow pit have been suspended often due to flooding, especially in the square closest to the rising swamp.

- The dark brown soil of the zig-zag ditch near the clay borrow pit.

- Archaeologists (clockwise from left) Hannah Barch, Caitlin Delmas, Josh Barber, Gabriel Brown and Sean Romo prepare the western foundations of the 1617 church prior to the installation of the glass portal.

- Archaeologists (clockwise from top left) Hannah Barch, Caitlin Delmas, Josh Barber, Ren Willis, Gabriel Brown and Sean Romo prepare the western foundations of the 1617 church prior to the installation of the glass portal.

- Archaeologists Natalie Reid, Gabriel Brown, and Anna Shackelford dismantle the well ring prior to the backfilling of the Governor’s Well.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens fills in the Governor’s Well.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford backfills the east churchyard excavations.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo gives an archaeology tour.

- Carpenter Jesse Robertson works on the Blacksmith Shop’s new chimney.

- Blacksmiths Shel Browder and Steve Mankowski examine some of the iron artifacts found at Jamestown. Their goal is to reproduce working reproductions of some of these artifacts in the Blacksmith Shop.

- The Livonian schilling retreated by Senior Conservator Dan Gamble

- The silver ear picker retreated by Senior Conservator Dan Gamble

- Bricks from the ninth course of the Governor’s Well. They are labeled so that their location in the course can be discerned.

- The 15th-century breastplate during conservation. It’s in a tub of silica gel that absorbs moisture from the armor after being removed from its sodium hydroxide bath.

- Another of the partial swords found in the Governor’s Well. This one is being conserved by Senior Conservator Dan Gamble.

- A bag of objects from the Governor’s Well that were caught by the 2mm screen during water screening. This bag has not yet been picked through by the volunteer team.

- A partially picked-through tray of objects found during water screening soil from the Governor’s Well.

- Associate Curator Janene Johnston holds a mortar-covered brick found during the Church Tower excavations.

- Some of the architectural artifacts found during the Church Tower excavations. Included are examples of granite, quartzite, mortar, and coral.

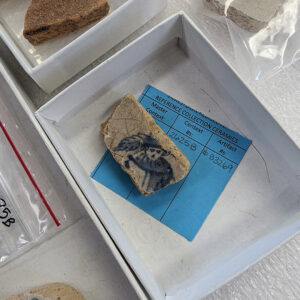

- A delft tile sherd bearing the likeness of a soldier

- The Jamestown delft tile collection. The Field School students will learn to mend ceramics using this assemblage.

- The three types of spangles in the Jamestown collection. Associate Curator Janene Johnston is organizing, cataloging, and conducting pXRF scans of each of the spangles to determine their elemental makeup.

- The Spanish olive jars in the Jamestown collection. Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens and Curatorial Intern Amanda Nedell are working to label, catalog, and then mend sherds from the same vessels.