At the 1607 Burial Ground the Jamestown Archaeologists are at work preparing the area for next month’s excavations of three colonists who died in the first few months of the colony’s existence. The burial ground, situated just inside the western palisade wall, was situated inside the fort so as to conceal deaths from the Virginia Indians, as instructed by the Virginia Company of London. This area is chock full of features, including postholes, cobble foundations, and a palisade postdating and separate from the fort’s western wall. The sheer number of features gives the area a mottled look similar to camouflage, indicating use and reuse of the land over many decades. A series of postholes defining a subterranean feature may be part of a cellar discovered in 2004. That cellar was full of late-17th-century wine bottles, and while digging in the northeast corner of the excavation area, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid found another one, broken, but appearing to be of the same style. The palisade cuts one of the graves, meaning it’s newer than the grave. The team found a test square excavated in the 1950s by the National Park Service. They are currently recording and excavating all of the features that need to be removed in order to access the burials. They’re bringing everything down to the same level so that ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys can run across the entire excavation area. The layer they’re going down to is prehistoric, and there are examples of worked lithics and sherds of Native ceramics sticking out of the ground in the areas where the archaeologists have already reached this depth, suggesting use of this area by Native peoples prior to the arrival of the colonists.

Several interesting artifacts have been found here in addition to the wine bottle. Two blue beads were found by Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis during her excavation of a large posthole thought to be related to the aforementioned cellar. She also found a coin weight in the same feature. Coin weights were unique to a specific coin and when used in conjunction with a scale validated the mass of metal in that coin. This harkens back to an era when a coin’s value was based on the metal it was made out of. If a silver coin was clipped (illegally) for instance, it was no longer worth the value printed on its face. The coin weight that Ren found was used for weighing a French gold coin known as an écu d’or. The coin features a shield decorated with fleur-de-lis, which was the coat of arms of the kings of France from medieval times. Other artifacts found here this month include several copper straight pins and a tiny bone die, similar to several others already in the Jamestown collection.

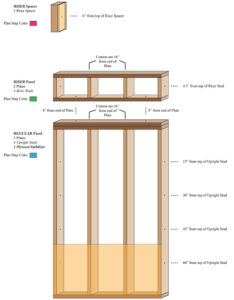

Just east of the Godspeed Cottage an assembly line has sprung up, with several of the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists trading their trowels for paint rollers. The team is painting wooden modular sections of burial structures, designed to house the team and protect human remains during next month’s burial excavations. The archaeologists decided to go a different route with the burial structures this year, using 6′ x 4′ wooden sections as a building block that can be combined to build any number of shapes — similar to a house of cards, though without the instability. All the painting outside the Godspeed Cottage is another component in this new approach, an effort to make the wooden sections reusable year after year. The outdoor, mold-resistant paint will hopefully slow the wood’s degradation, allowing the team to use it year after year, saving time and money. Another benefit of this modular approach is the portability of the 6′ x 4′ wooden sections. The team has learned through years of doing this that it’s difficult to move and work with large wooden walls, often requiring a team of people to raise and position them. The new 6′ x 4′ sections can be easily carried by a single person, and will be joined to each other using a uniform series of bolts.

The archaeologists are also running out of conveniently spaced burials in the 1607 Burial Ground to excavate. Every fall three burials are excavated there, and typically they choose three that are close to each other so as to be more easily encompassed by the burial structure. Well after years of burial excavations, the conveniently situated groupings are getting harder to find. Because of the flexibility provided by the 6′ x 4′ sections however, the task of building a structure that outlines irregularly-shaped excavation areas isn’t as daunting. One side of the structures will be built slightly taller than the opposite wall, creating a slight slope for the overlying roof that will allow rain to slide off rather than pool and possibly cause leaks.

A second structure will house the burial excavation in Smithfield, in an area just south of the Archaearium. This area now regularly floods, creating wet/dry cycles that damage archaeological features and human remains that inhabit it by the dozens. A rain event here this month caused flooding at these excavations. The sandbags lining the site prevented rain from getting in via the surface, but it instead got in via the saturated soil comprising the excavation area’s walls. The skeleton excavated last year just a few feet away from where this year’s colonist lies was in awful shape, with only the skull and portions of the arms surviving. All that remained of the rest were stains in the ground. The team is hoping that the colonist slated for excavation this year will be in better shape. Preliminary data from several ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of the burial is not promising. Directory of Archaeology Sean Romo could not discern a skeleton when analyzing the data, but he stressed that several factors can “muddy the waters” of the GPR data and only traditional ground-truthing via shovels and trowels will reveal its condition with certainty. Additionally, as the crew excavates down into the burial, several more GPR surveys will be taken so as to gain as much information about the remains’ position in an effort to avoid damaging them with their trowels and other tools.

Speaking of GPR, the archaeological team was excited to receive a new GPR machine in September, this one having a 1500 MHz antenna. The machine was donated by board member CarolAnn Babcock, a long time generous benefactor of Jamestown Rediscovery. During last year’s burial excavations, the team achieved the best GPR data of the burials using a machine with a 1500 MHz antenna, borrowed from collaborator Geographical Survey Systems, Inc. (GSSI). They are eager to put this one through its paces . . . there will be no shortage of opportunities to use it during the burial excavations next month.

Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe is mending a large London post-medieval redware jar. Three sherds of the jar’s base found last year mend with this jar and in order to insert them where they belong, the entire vessel needs to be taken apart first. The jar is tall, almost 10 inches (28.5 cm), and is of varying thicknesses. The base is imperfectly flat, having a slant that makes the jar lean slightly when upright. Jo has found mending the vessel more difficult than most, due to its large size (and weight), it’s incompleteness, and its high porosity.

To give stability to the vessel while the mending adhesive (B72) solidifies, Jo is using bags of sand as weights and painter’s tape to adhere it to the plastic tub it’s sitting in. Because of the incomplete manner of the vessel, heavier sections near the top are precariously supported, making mending difficult and lending it to tipping over or collapsing without additional support. While it would be quicker to mend two partially-complete sections together, Jo is necessarily mending one piece at a time so as not to apply too much weight to a new mend and have it shift or even collapse while the B72 is drying. Because the vessel is so porous, it absorbs a lot of B72, requiring repeated applications. The jar is a good example of a cross-mended object, that is its pieces come from a variety of archaeological contexts. Sherds of the vessel have been found in the East Bulwark, the West Bulwark Trench, Pit 3, and the First Well. The newest piece was found in the fort’s eastern palisade trench in a section that currently runs through the Church Tower, built around 1680, decades after the palisade was torn down.

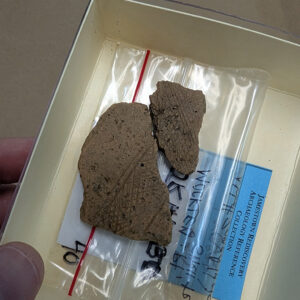

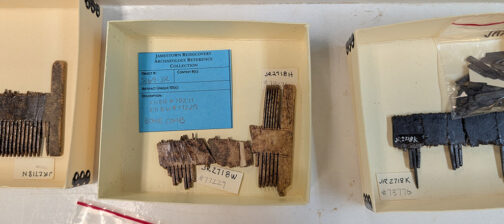

Curatorial Intern Molly Morgan continues her work mending Native ceramic sherds. This month she has focused her efforts on two Potomac Creek vessels, one of which was on display in the Archaearium museum but has been removed for this project. Molly has found at least seven new sherds that mend to the vessel on display, meaning it will be substantially more complete when it is put back into its exhibit case. Potomac Creek is a ceramic type made with crushed quartz temper by members of the Patawomeck Tribe. Both vessels are collared jars with rounded bottoms and both have distinctive dowel-impressed decorations at the rims.

Jamestown was happy to welcome Sarah Steele back to the island. Sarah is one of the world’s foremost experts on jet, a wood-based jemstone formed through millennia of geological processes. The term “jet-black” is a reference to this material. Sarah is visiting Jamestown to further study the jet and jet-like objects in Jamestown’s collection, of which there are just over forty in number. Among the artifacts she is examining are a series of crucifixes, beads, knife handles, and a gaming die. Though this visit was primarily to get a final look at the artifacts before the publication is finalized, two new beads were added to the study. These were found and cataloged by Emma Derry this month during picking of material from Midden 1, a trash deposit dating to the mid-to-late 17th century. As part of her research Sarah is trying to ascertain if a scientific determination can be made that differentiates jet and jet-like objects. Another focus of the research is determining where the jet itself came from, with two possible candidates being Whitby, England and Asturias, Spain. She is collaborating with Yale’s Dr. Richard Hark who is performing isotopic analysis on the objects she is studying and is a co-author on the forthcoming publication of their findings.

During her visit, Sarah used micrographs (photographs through a microscope) to identify several of the objects as wood, likely jet, or jet. The black gaming die was identified as wood. All of the data derived from Sarah’s efforts expands our knowledge of the collection and is recorded by Associate Curator Janene Johnston into our artifact database. This is a good example of how outside research on the Jamestown collection benefits the researcher and adds to our knowledge about the colonists and the objects they brought with them.

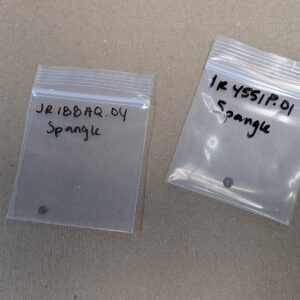

Associate Curator Janene Johnston is cataloging artifacts from the Seawall excavations of 2021. This data will be part of an archaeological report on the dig which was located close to James Fort’s eastern bulwark. Many of the artifacts that Janene is cataloging were recovered from strata associated with a midden, an area where trash was deposited. Among the artifacts Janene is cataloging are sherds of Portuguese redware, including a small lid piece, and three large sherds of Spanish olive jar, including one that may mend with a large vessel housed in the oversized storage cabinet in the Vault. The archaeologists also found a sherd of Frechen ceramic, a piece of the medallion from a Bartmann jug. This medallion bears the coat of arms of Maurice, Prince of Orange, an important Dutch figure in the Eighty Years War. Also found during the Seawall excavations are two spangles, one round, and one teardrop-shaped. Spangles were used to decorate clothes and other textiles and resemble modern sequins. Spangles have been found in ones and twos at Jamestown, but dozens were discovered as part of the Captain’s Sash accompanying the burial of Captain William West.

Janene is also cataloging some new finds from the current cellar excavations, a structure discovered by GPR in 2023. A sherd of delftware found there may belong to a fragmentary cat jug in the collection. Three sherds of the vessel exist and the coloring, fabric, and tin glaze suggest it could be a fourth. These hollow, molded vessels were painted to resemble cats and are extremely rare. Less than a dozen intact examples of these 17th-century jugs are known to exist.

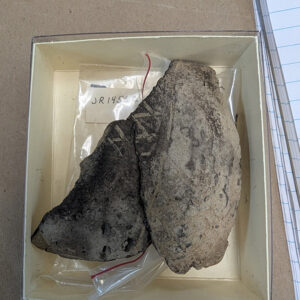

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp has only nine more layers to go in her sorting of objects from the First Well. So far she has found over 600,000 bones, a record of what the colonists were eating during a fairly well defined period of time. The well was built in late 1608 or early 1609 and was filled with trash prior to 1611, probably during Lord de la Warr’s cleansing of the fort in June, 1610. Like other wells at Jamestown the first one was used as a trash pit once its water went bad. This trash, now called “artifacts” as a consolation for spending 400 years underground, is invaluable to our archaeological and collections teams. Two mammal bones, likely deer, caught Magen’s fancy this month. One of them bears butcher marks, indicating the animal was eaten by the colonists. Another bears the marks of canid teeth; maybe somebody was rewarded for being a good boy.

Glass beads have been at the forefront of Associate Curator Emma Derry’s mind in September. She is reorganizing them, rehousing the collection to make the beads easier to find and easier to build off of previous research. Emma is also implementing changes to the way outside research and loans are recorded. In an effort to have all of the data about an artifact in a single place, Emma and the curatorial team have committed to entering all research data and information about loans to outside institutions in the database’s artifact record. This is a bit more work up front but saves time in the long run as information doesn’t need to be pulled from a variety of sources to have a complete record of the artifact in question.

related images

- Contractor Tim Schmidt removes the top layers of the 1607 Burial Ground excavation site. The area was previously excavated about twenty years ago and the top layers are backfill from those excavations.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford and Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discuss the excavations at the 1607 Burial Ground.

- The excavations at the 1607 Burial Ground

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas takes measurements of a palisade that cuts (and thus postdates) several features in the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discuss a large posthole feature they found during the 1607 Burial Ground excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Director of Archaeology Sean Romo conduct a GPR survey of one of the burials in the 1607 Burial Ground. Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid conduct excavations at the rear. Natalie’s dust pan contains a partial wine bottle she discovered during her digging.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis, and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas conduct excavations in the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Excavations at the 1607 Burial Ground

- The archaeology team removes the backfill at the 1607 Burial Ground. The black filter fabric on the ground was placed there in the 2000s by archaeologists after completing their excavations to protect the archaeological resources underneath.

- Staff Archaeologists Caitlin Delmas, Gabriel Brown, and Natalie Reid pose for a drone shot at the 1607 Burial Ground

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith and Staff Archaeologists Natalie Reid and Caitlin Delmas conduct excavations at the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Staff Archaeologists Gabriel Brown, Natalie Reid, and Caitlin Delmas at work in the 1607 Burial Ground. The row of cobblestones is a foundation for a row house likely built in 1611. The modern recreation marking the foundation can be seen to the left of Gabriel.

- Staff Archaeologists Natalie Reid and Caitlin Delmas and Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith at work in the 1607 Burial Ground. Caitlin is excavating cobbles that served as a foundation for a ca. 1611 rowhouse because they will prevent access to the earlier burial beneath them.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb excavates and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid prepares for survey work at the 1607 Burial Ground.

- An animal bone with butchering marks found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations

- Staff Archaeologists Natalie Reid and Caitlin Delmas at work in the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid examine the wine bottle found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations.

- Pieces of a wine bottle found by archaeologists excavating in the 1607 Burial Ground. This bottle likely dates to the late 17th century. A wine cellar dating to that period was excavated in this area in 2004 where several other similar bottles were found.

- Director of the Voorhees Archaearium Archaeology Museum Jamie May examines a wine bottle found in the 1607 Burial Ground. The bottle is likely related to a series of late 17th-century wine bottles found in a nearby cellar in 2004. Jamie was one of the archaeologists who excavated that feature over two decades ago.

- A partial wine bottle found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discusses the excavations at the 1607 Burial Ground with a group of schoolchildren.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith shares an artifact found in the 1607 Burial Ground with some visitors.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford shares an artifact found at the 1607 Burial Ground with visitors.

- A bone die found at the 1607 Burial Ground site

- Some straight pins, a tack, and a bead found in the 1607 Burial Ground

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds a sherd of delftware she found while excavating in the 1607 Burial Ground.

- The neck and part of the body of a wine bottle found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations. The bottle is likely from the late 17th-century and related to a wine cellar discovered in 2004.

- A smattering of artifacts from the 1607 Burial Ground including animal bone, a bead, and a straight pin.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo holds one of the modular 6′ x 4′ wooden sections used to build the burial structures.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford backfills part of the excavations just south of the Archaearium. Only the sections involved in the upcoming burial excavations were left open.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid perform a GPR survey of the burial excavation area south of the Archaearium. The burials are the long rectangles in the soil (scored in this photo).

- Staff Archaeologists Ren Willis and Natalie Reid at work at the excavations west of the Archaearium

- Fish vertebrae found in the excavations west of the Archaearium

- Portuguese faience sherds found at the excavations west of the Archaearium

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber cuts posts for use in the burial structures.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch and Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown painting boards that will comprise the two burial structures used this fall.

- The team works around a large drainage pipe installed to prevent flooding at Fort Pocahontas (seen at rear). A smaller pipe running left/right in the photo used to provide water to a horse trough that has since been relocated.

- The archaeology team discusses upcoming projects in the Godspeed Cottage.

- Collections Assistant Lindsay Bliss uses the flotation tank to process excavated soil samples. The machine separates objects based on density and can capture tiny objects such as seeds other botanicals.

- Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe uses bags of sand and painter’s tape to stabilize the LPMR jar while a mended section’s adhesive solidifies.

- A large mammal bone bearing canid teeth marks

- Two spangles found in the Seawall excavations of 2021

- A faunal bone artifact, perhaps part of a ring, found by Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp during picking through objects from Jamestown’s first well.

- A sherd of a Bartmann jug found in the cellar excavations. This piece is a partial medallion bearing the coat of arms of Maurice, Prince of Orange.

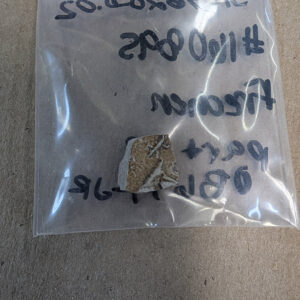

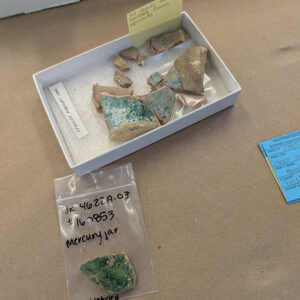

- At bottom is a sherd of a Spanish majolica mercury jar recently found in the cellar excavations. In the tray above it are several other sherds of one such jar. It is unknown if the new piece belongs to the vessel in the tray.

- Two jet beads found in the 2021 Seawall excavations

- A Spanish olive jar rim piece is held by Associate Curator Janene Johnston. This piece was found during the Seawall excavations of 2021.

- A lid piece of Portuguese redware found in the Seawall excavations of 2021

- Two sherds of Portuguese redware being cataloged by Associate Curator Janene Johnston. These were found during the Seawall excavations of 2021.

- A sherd of delftware found in the cellar excavations. This may belong to a partial cat jug already in the collection.

- Associate Curator Janene Johnston shares horse related artifacts during an update for volunteers.

- A sherd of Native ceramic among those being examined by curatorial intern Molly Morgan. This one contains a drilled hole.

- A partial lug handle from a Native ceramic vessel

- Two mended sherds of Native ceramic of the Rappahannock Incised Townsend type

- Two sherds of Native Townsend ceramic found in Pit 1

- Two mended rim sherds of Native ceramic

- A partially mended Native ceramic vessel. Curatorial intern Molly Morgan is looking for additional sherds that mend to this object.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds a partially mended Native ceramic vessel. She’s sharing artifacts during an update for volunteers.

- A sherd of Chinese porcelain found at the 1607 Burial Ground

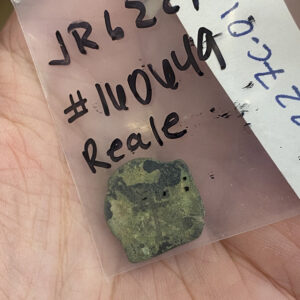

- A silver Spanish real coin found at the cellar excavation site

- Smithfield is increasingly flood-prone and the wet/dry cycles are damaging the archaeological resources below the surface.