The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists have successfully excavated the remains of four colonists, three from the 1607 burial ground and one from Smithfield, the field northwest of James Fort. The process was one of many moving parts and tight deadlines as stages of the excavations needed to be completed prior to the arrival of outside colleagues lending their expertise.

There are a large number of burials in and near Smithfield. Over 100 are clustered on Statehouse Ridge, where the Archaearium now stands, and an additional 18 were found during our recent excavations in Smithfield. The limits of the burial ground have not yet been reached, and our southernmost 15’x15′ square contained three closely-spaced graves. The burial ground is thought to have been used as early as 1610 and into the 1640s, and so likely contains a multitude of graves. Normally, the archaeologists do not disinter individuals from this cemetery. However, Smithfield is “bowl” shaped, and sits significantly lower than Statehouse Ridge. Smithfield floods with regularity now, something it didn’t do when the Jamestown Rediscovery project started in 1994. This flooding causes wet/dry cycles that damage human remains. This year, the archaeologists decided to assess the damage done to the human remains in Smithfield. It is important to know what damage the water has caused thus far, so the team can plan ahead for future work in Smithfield and other low-lying spaces.

The remains were in poor condition, with most of the body dissolved into the soil, leaving behind only stains in the outline of a skeleton. Despite this deterioration, the body staining showed the layout of the individual in the grave, and indicated they had likely been shrouded. The skull was still present, its survival perhaps aided by the fact that it was resting against the east end of the grave shaft a few inches higher than the rest of the remains and thus a few inches higher than the groundwater just beneath the burial. Clay kept the skull together in the ground and during removal to the lab. The left humerus is the only other bone that survived beyond tiny fragments. Soil samples were taken where various parts of the body would have been, including the lungs, the stomach, the intestines, and the colon. These samples will be investigated for the presence of pollen and phytoliths that could give clues to the colonist’s diet. Additionally Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins worked with the excavators—Archaeological Field Technicians Josh Barber and Hannah Barch, and Director of Archaeology Sean Romo—to select areas for elemental analysis. He then used a portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) machine to take readings at various depths of the excavation away from the remains, to act as a control. These readings will be analyzed in the coming weeks. Inside this excavation square there were two postholes that don’t seem to be related to the burial. The postholes are likely fenceposts, as they aren’t substantial enough to be part of a building. These will be recorded on our excavation map like all other features. Perhaps future excavations nearby will reveal other postholes related to these, giving shape to their function.

A few feet away, excavations are picking back up on the western excavation squares just south of the Archaearium. In June, a possible fort-period building was found here, its remains resembling a building discovered in the middle of James Fort. That interpretation is now in question, as the team exposes more of the feature. Notably, archaeologists were able to conclusively determine that the feature cuts an earlier burial. This burial, and another recently exposed nearby, appears to be brick-lined, a style of interment dating to the 1650s or later. Since the possible foundation cuts the burial, it now looks like the potential building dates to after 1650. This type of reassessment is common in archaeology, as new discoveries give insight into past finds and update interpretations. Excavations in the next few months will hopefully further refine the chronology of this space.

Over at the fort, just inside the western palisade wall, a series of three burials were excavated as well. These individuals died within the first few months of the colony’s existence and the fact that they were buried inside the fort is no coincidence. The settlers were instructed by the Virginia Company of London to hide the sick and dead so that the Virginia Indians wouldn’t learn of the weakening of the colony:

“Above all things do not advertize the killing of any of your men, that the country people may know it; if they perceive that they are but common men, and that with the loss of many of theirs, they may deminish any part of yours, they will make many adventures upon you.”

Charters of the Virginia Company of London

Captain John Smith wrote that 50 colonists died between May and September of that first year, and 36 burials have been found by the archaeological team here, some being double burials, and one even containing three individuals. Some colonists’ remains have been lost to the James River, prior to the construction of the seawall in the first years of the 20th century. Samuel Yonge, engineer of the seawall that undoubtedly saved much of James Fort and prevented other colonists’ remains from eroding into the James wrote in 1896:

“It is credibly stated that when the bank thus exposed was undermined by the waves, several human skeletons lying in regular order, east and west, about two hundred feet west of the tower ruin were uncovered. On account of their nearness to the tower it seems quite probable that the skeletons were in the original churchyard. One of the skulls had been perforated by a musket ball and several buckshot, which it still held, suggesting a military execution. Soon after being exposed to the air the skeletons crumbled.”

Samuel Yonge

This graveyard that Yonge is referring to is the 1607 burial ground where October’s excavations took place, lying 200 feet west of the 1680s Church Tower. Every year the archaeologists, conservators, and curators commit to excavating, conserving, and analyzing three burials from this location. Prior to excavations in the early 2000s, the burial ground was covered by several feet of earth, ramparts from Confederate Fort Pocahontas. The Confederates and their enslaved laborers unknowingly built Fort Pocahontas in 1861 on the same high ground where the colonists built their fort 254 years earlier. These earthworks were excavated by the team in the first decade of the 21st century in order to reach the 17th century archaeological resources underneath. The team discovered the burial ground shortly thereafter, but the graves are now only a few feet from the surface, without the earthen shield that had protected them from rainwater for 140 years. The team is keen to learn as much as they can about these earliest colonists before they dissolve into the soil of their unmarked graves.

Of the three excavated this year, the individual closest to the river appears to have been in his late teens when he died, based on examination of his teeth. All individuals excavated from this area should be male as the graves here date to before women were sent to the colony. Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas excavated these remains, inside an unusually wide grave shaft. It was wide enough that it was surmised that it could have been a double burial, but ground-penetrating radar (GPR) disproved that idea prior to trowels reaching the remains. The skeleton was in fair to poor shape and was missing its toes, likely dissolved into the surrounding soil. The thin stature of his arm bones may indicate that his life was not filled with hard labor.

The next grave to the north held another skeleton in fair to poor shape. This individual appears to be a pre-teen, approximately 10 years of age. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis excavated this burial and found most of the ribs missing, the vertebrae to be highly deteriorated, and many of the other bones very brittle, collapsed, and broken. He still had some of his baby teeth, an indicator of his young age.

The last burial this year, just to the north of Natalie’s and Ren’s, was the only adult and the best preserved. The grave shaft was just a bit too short for the individual…his feet are pressed up against the wall and his head is also elevated, likewise held up by the shaft’s wall. Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford and Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown excavated this individual, and found his bones to be robust. This burial was the only one to contain any artifacts. An aglet, a metal tip attached to string to prevent fraying and ease threading (much like the hard plastic tip of a modern shoestring), was found near the colonist’s feet, and is strong evidence that this individual was shrouded. The string in this case would have tied the shroud to prevent it opening during burial preparation and interment. Another artifact, an ancient projectile point was also found in the burial shaft, likely unrelated to the colonist and escaping notice of the men digging and filling in the grave in 1607.

All of the remains will undergo isotopic testing, with stable isotopes of several elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen giving clues to diet and location of origin (Read more about isotopes and what they can tell us about an individual). The bones will also be tested for lead levels, with a correlation existing between high lead levels and high status due to eating and drinking from vessels such as lead-glazed ceramics and pewter containing the toxic metal.

The process now shifts to the lab, inside the Rediscovery Center, where the archaeological conservators and curators are painstakingly conserving, analyzing, and cataloging the bones, and taking samples for isotopic testing and DNA extraction.

In the Vault, Associate Curators Janene Johnston and Emma Derry have been reexamining Jamestown’s organic bead collection after a realization that some of them may actually be button cores. A detailed look at the eight thread-wrapped buttons in the collection reveals a wooden core around which the threads are wrapped. It’s possible, and perhaps probable that several of the wooden beads are instead these wooden-core buttons without surviving threads. It’s also possible, though less likely, that some of the bone beads served the same purpose. Shape is an important determining factor in the classification, with domed “beads” more likely to be button cores. The two curators are poring over the beads and buttons and are preparing their findings for presentation at the Southeastern Archaeological Conference this month in Williamsburg.

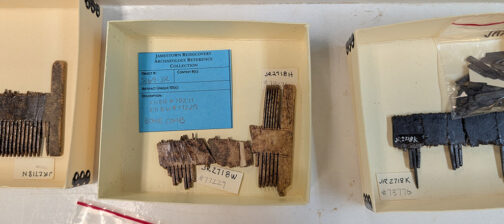

Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens spent some of October continuing work on crucibles. As discussed in last month’s dig update, the crucibles are being crossmended in order to determine how many crucibles in total were present at the site, the distribution of crucible sizes and shapes, and to better understand the contexts from which the fragments came. Ultimately some of the mended vessels will form part of the Jamestown Reference Collection, which represents the breadth and depth of all of the material recovered by Jamestown archaeologists from 1994-today. Reference Collection artifacts are kept in the vault for easy access for research and as cataloging reference material. Working in collaboration with Senior Curator Leah Stricker, Lauren has mended 47 distinct crucibles this month alone!

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp continues her work with animal bones from the fort’s first well, the “John Smith Well”, as it was constructed while he was president of the council in late 1608 or early 1609. Like most wells at Jamestown, it was used as a trash pit once its water went bad. And luckily for us, the well was in that stage of its life during the Starving Time, giving us a snapshot into what the colonists were eating to survive when they were under siege by the Powhatan people. Magen has completed her sort of layer “N” of the well, chock full of bones of all types. Over 70,000 bones have been counted in that layer so far and the team approximates there will be 150,000 by the time they’ve all been tallied. Once Magen’s work is complete, the bones will go to contract Zooarchaeologists Stephen Atkins and Susan Andrews, who will look for details such as butchery patterns, signs of burning, age, and sex. They will also further categorize the bones by species where possible.

Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe is assessing the condition of artifacts stored in the Dry Room, a room adjacent to the Vault that is kept at a controlled temperature and humidity to prevent deterioration of iron materials. Jo is also taking measurements, placing paper tags printed from the database with the artifacts, rebagging the artifacts, and organizing them in the drawers to conserve space. So far she has completed work on jack plates and has been working on fish hooks, which range in size from about an inch to more than six inches in length!

Our curators have recently cataloged the partial pipe that was found this past summer just south of the Archaearium by an attendee of the annual Kids Camp. The lead glazed, red earthenware pipe was molded into George Washington’s head with a crown at the bowl rim. Washingt- is stamped on the underside of the stem. There is another partial stamp of a “p” on one of the sides as well. This clay pipe is most likely a Stummelpfeifen, or “stub pipe,” made in Germany (Uslar or Grossalmerode) for exportation to America between 1836-1856. They made other figural pipes at the time that could have been for a presidential candidate or were commemorative like this George Washington pipe. This type of pipe became popular for American companies to reproduce, but the German pipes can be distinguished from their American counterparts by the angle that the stem protrudes from the bowl; pipes with a 45º angle were made in Germany and the pipes with 90º angle to the bowl were made in America.

dig deeper

related images

- The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists build the burial structure that will protect the burial just south of the Archaearium as it is being excavated.

- Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown builds the burial structure at the 1607 burial ground.

- The chimney base of a ca. 1611 building built in the same location as the 1607 burial ground. The hearth was excavated in order to access the westmost grave.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid carefully excavates the chimney base of a ca. 1611 structure built on top of the 1607 burial ground. The chimney base needed to be removed in order to excavate a burial there.

- Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford use ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to survey one of the graves at the 1607 burial ground.

- GSSI’s Peter Leach and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid use ground-penetrating radar to “see” the burial below the surface. Note the stick figure etching on the grave approximating the location of the individual.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo examines the results of a ground-penetrating radar scan of one of the graves at the 1607 burial ground.

- GSSI’s Peter Leach shares the results of the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of the burials with the archaeological team.

- The three burials at the 1607 burial ground. The leftmost one is unusually wide leading to speculation that it might contain two individuals. It did not.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, and Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Ann Hartley excavating inside the burial structure at the 1607 burial ground. The graves are the three dark rectangles.

- Staff Archaeologists Caitlin Delmas and Natalie Reid, Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis, and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford excavate the three burials at the 1607 burial ground.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid examines a printout of the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) results to use as a guide during her burial excavations.

- The archaeological team’s excavations come close to exposing the human remains at the 1607 burial ground.

- Excavations at the 1607 burial ground prior to exposing the remains

- A sherd of Virginia Indian pottery found during the burial excavations at the 1607 burial ground

- The archaeologists prepare for excavations in the 1607 burial ground.

- The team suits up prior to beginning the day’s burial excavations.

- A projectile point found while excavating one of the graves in the 1607 burial ground

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis, Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, and Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber are finding excavations at Smithfield difficult after a flood.

- Possible button cores long thought to be beads

- A crucible with many mends thanks to the efforts of Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens. The tape is a temporary measure. Paraloid B-72 will be used as an adhesive once the team is satisfied all sherds belonging to the vessel have been found. The adhesive is reversible, so if future excavations find more pieces, it can be taken apart to add them without damaging the object.

- Two smaller fish hooks in the collection

- A large fish hook housed in the dry room. This is part of the collection being assessed by Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe.

- A camper holds a clay pipe bowl he found during his excavations.