In the southwest corner of James Fort, in a structure resembling a greenhouse, the lights were on well past sunset several nights this month. Inside, the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeological team was preparing three burials from the 1607 burial ground for the arrival of outside experts — in the fields of ground-penetrating radar and forensic anthropology — to assist them in the excavation of the remains. Samples of the remains are being prepared for transport to the ancient DNA lab at the University of Connecticut for DNA extraction and analysis. The loud, high frequency sound of gasoline-powered vibracoring could be heard from the Pitch and Tar Swamp this month as UConn’s Dr. David Leslie took several deep samples of soils north of the fort. We hope that analysis of the soil will shed light on the industrial and husbandry practices of the settlers. The curatorial team has been busy analyzing and conserving buttons in the collection, searching through artifacts from the fort’s second well to look for faunal material, and studying antique firearms in preparation for preparing our reference collection. They also hosted a small finds workshop focused on locally made 17th-century pipes. Among the conservation team’s work this month is the mending of a case bottle found in a cellar of the fort’s 1608 extension. They also hosted Dr. William Taylor from the University of Colorado who is conducting a number of tests on our horse remains as part of a study on the spread of horses throughout the Old World and the New.

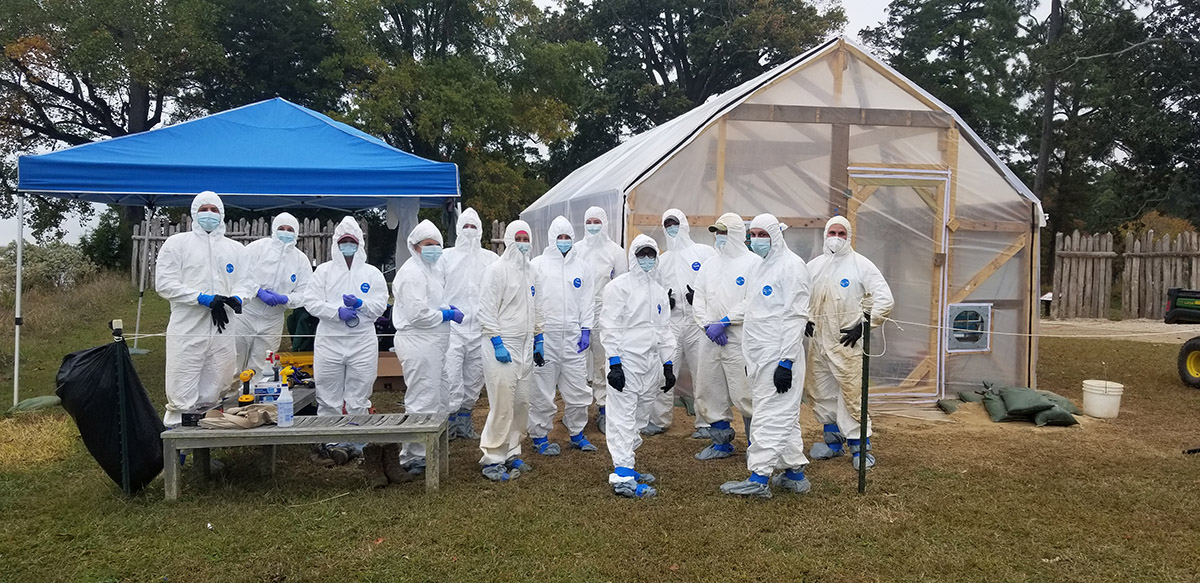

Donning Tyvek suits and masks to avoid contaminating ancient DNA with their own, the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists carefully excavated the remains of three early fort-period settlers this month. Buried within James Fort’s walls to hide their dwindling numbers from the local Virginia Indians, these burials were among 31 found in the southwest corner of the fort during excavations in 2006. Of those found, 13 have now been excavated.

Before the trowels met the ground, several preliminary steps were taken to make the excavations as successful as possible. Great care is taken by the archaeological team to protect human remains both from the elements and from contamination from the DNA of the excavators themselves. The settlers have been in the ground for over 400 years and during that time their remains have reached equilibrium with their surroundings. Exposing them to the surface can be detrimental to their preservation and as such care is taken to minimize contact between the remains and the weather. A wooden shed, clad in plastic sheeting and waterproofed with sandbag foundations, was built to encapsulate the excavation site.

With a structure in place, the archaeologists next set out to determine if ground-penetrating radar (GPR) could be of benefit to the excavations, possibly informing them of the location and depth of the remains within the grave shaft. Peter Leach, an archaeologist and GPR expert from Geophysical Survey Systems, Inc. was asked to consult on the project, the latest in a series of collaborations between him and Jamestown Rediscovery. Mr. Leach conducted surveys on all three burials and a very complete picture of the remains was formed when pieced together by GPR imaging software. The team now had a blueprint for their excavations that would aid them in the delicate process ahead.

Over the course of a week the burials were excavated, bit by bit, often exchanging trowels for more delicate tools so as not to damage the remains. There were postholes cutting through each of the burials that were from later buildings though luckily none were deep enough to damage the remains. Each of the burial excavations was led by senior members of the team. David Givens, Director of Archaeology, led the excavations on one of the burials. Mary Anna Hartley, Senior Staff Archaeologist, led another, and Sean Romo, Senior Staff Archaeologist, led the third. Each lead had other archaeologists assisting. Dr. Chuck Durfor, archaeologist and staff photographer, has been documenting every stage of the burial excavations using both traditional photography and 3D photogrammetry. The techniques Chuck uses for 3d photogrammetry produce location accuracy within 1/5 of an inch and provide an interactive, rotatable view of the excavations.

This burial work provides Jamestown Rediscovery the opportunity to work once again with forensic anthropologist and professor Dr. Ashley McKeown of Texas State University. Dr. McKeown is an expert in osteology who has conducted field work and research all over North America. Previously at Jamestown she helped excavate burials inside James Fort and at the Statehouse site. We’ll be working hand-in-hand with Dr. McKeown throughout the process of excavation and analysis.

After excavations are complete and samples of the remains are prepared, members of the archaeological and conservation teams will bring the samples to the University of Connecticut. There Drs. Deborah Bolnick and Raquel Fleskes will extract DNA and perform analysis at UConn’s DNA lab. A series of comparisons can then be made, both between these individuals and others buried at Jamestown, and between these individuals and the greater population, both deceased and living. While definitive identification is difficult and rare, more general conclusions can be made about a person’s ancestral origins. Additionally, this is a rapidly-advancing science, with techniques available today that weren’t a decade ago. Future breakthroughs in extraction, refinement, and analysis will undoubtedly aid our research.

Another exciting development this month was the arrival of Dr. David Leslie, also from the University of Connecticut. Dr. Leslie is an expert in vibracoring, a process in which long metal tubes are vibrated and pushed down into saturated or semi-saturated earth to collect soil samples from several feet below the surface. The high frequency vibration, powered by a portable gasoline engine, helps to draw water down around the tube, lubricating it and the surrounding soil to help the tube reach the required depth. Once the samples were pulled back out with a truck jack, they were sealed for transport back to UConn for analysis. Dr. Leslie and our archaeologists took several samples from the Pitch and Tar Swamp in the hopes that signs of man-made change will be observed in the soil layers related to the early years of the colony. Industrial activities such as blacksmithing or glassmaking produce telltale elements related to those industries in the off-gasses they produce. These elements then settle on the ground and are what we are hoping to find in the soil samples. Similarly the presence of livestock can transform the soil through their feces. Elevated levels of nitrogen or phosphorous could give clues as to where the colonists kept their animals and possibly even information about the livestock itself.

Dr. Leslie archives half of each sample for future analysis and tests the other half. The soils are tested in 2cm to 5cm increments using portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (pXRFS). This process uses X-rays in a sort of call-and-response process whereby X-rays are beamed into the sample and the elements in the soil emit X-rays back. Each element has a characteristic X-ray response and this is used to identify the makeup of the soil. We’re grateful to be working with Dr. Leslie and will post the results of his analysis in future updates.

In preparation for tackling the firearms portion of the reference collection, Assistant Curator Janene Johnston attended the Archeology of Firearms conference hosted by the National Park Service at the Springfield Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. Janene studied different parts of firearms, residues left by their use, different flint and shot types, and also made connections with other institutions and researchers in the field. Janene and much of the curatorial team also attended a small finds workshop hosted by Jamestown’s Senior Curator Merry Outlaw and focused on 17th-century pipes. Curators from institutions across the mid-Atlantic region attended the workshop to learn from each other’s collections. These meetings give the attendees a chance to share knowledge and see a broader sample of artifacts to help in their identification and preservation.

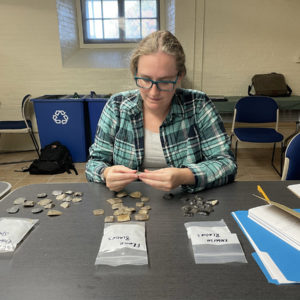

We are happy to have three interns working with us this month. One of our curatorial interns, Ava Geisel, is a student at Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School. She is helping us with the button reference collection in an effort funded by the Colonial Dames of America. Ava is working with Assistant Curator Janene Johnston to analyze buttons found at Jamestown. We have over 700 buttons in our collection, ranging from the 17th to the 21st century. While Ava is physically organizing, classifying, and recording the buttons, Janene is going through existing collections records in our database to ensure there is consistency in our data and that all notable traits are captured. Our conservation intern, Jackie Bucklew, is helping conserve some of these buttons and is also currently mending an early 17th-century case bottle found in a cellar in the 1608 fort addition. Our other curatorial intern, Lindsay Bliss, a master’s student from William & Mary, is sorting through artifacts found in the fort’s second well. She is looking for additional faunal material to send to outside consultants who are currently working on finishing up species identifications of animal bones from the second well. These zooarchaeological specialists previously completed an analysis of about 100,000 bones from this feature, uncovering evidence for changes in food stability during a period when Martial Law was instituted by leaders at Jamestown. Because the colonists used fouled wells as trash pits this will help us identify the colonists’ diets between the well’s construction in 1611 and 1617-19 when the well was filled in and sealed.

Dr. William Taylor, a professor, archaeologist, and curator from the University of Colorado, visited our lab this month. Dr. Taylor’s research focuses on the relationship between humans and animals, with an emphasis on horses and animal domestication. Almost all of the horse remains in the Jamestown collection show signs of butchering, fire, or both as the first seven horses sent to the colony were eaten during the Starving Time. Dr. Taylor’s goals include photography and 3D scanning of the horse remains in our collection as well as minimally-destructive sampling of some of the remains for radiocarbon dating, ancient DNA sequencing, and stable isotope analysis. The DNA analysis will include comparisons to modern and archaeological horses in both Eurasia and North America, in order to understand how horses spread across the ancient world during the last 500 years. The stable isotope analysis of oxygen, strontium, carbon, and lead can give insights into a horse’s feeding, mobility, and care, and may help understand how the first horses made their way to Jamestown, and their impact on early life in America. We’re excited to work with Dr. Taylor on this project and look forward to seeing the results.

Some exciting finds have come in from the field this month. A gold ring found was found in the excavations near the Pitch and Tar Swamp. There are over 60 finger rings in the Jamestown collection, but only 7 are made of gold. This is an extremely rare find here on the site. This ring is called a poesy ring, which refers to the poem-like lettering inscribed on the interior of the band. It’s only partially visible in the photo, but the letters read: “As endl- is my love”. The second word should be “endless,” but there is limited room on the small band and the jeweler may have shortened the word! There are no other markings on the interior band. The ring is broken and slightly bent out of shape, but if it was intact, it would measure 54mm in circumference, making it just smaller than a modern size 7 ring.

The clasped hands on the ring is a fede motif. Used as early as Roman times in wedding ceremonies, the clasped hands represent friendship, love, faith, loyalty, trust, and connection. The term fede likely came from the Italian phrase “mani in fede,” which translates to “hands clasped in faith.” Common in the 17th century, clasped hand rings have been found on other archaeological sites of the period, including in Virginia and in museum collections around the world.

Another find of note is a projectile point found in the fill above one of the burials excavated this month. It’s a contact period point so it could have been made around the time of the colonists’ arrival. Lastly, a Groningen token was found during the excavations north of the Church Tower. Almost twenty of these tokens have been found at Jamestown; this one was made in 1590. You can read more about these tokens here.

related images

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo, Archaeological Field Technician Brenna Fennessey, and Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley trowel away the layers above the three burials.

- The team discusses the upcoming GPR surveys with Peter Leach of GSSI.

- Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown and Dr. David Leslie use a truck jack to extract the vibracore tube from the swamp.

- Participants in the 2022 Archeology of Firearms conference

- Assistant Curator Janene Johnston inspects different types of gunflints at the 2022 Archeology of Firearms conference.

- Attendees of the small finds workshop examine a pipe bowl.

- Virginia Indian pipe sherds shared at the small finds workshop.

- Intern Ava Geisel measures the diameter of one of the buttons in the collection.

- Some of the horse remains in the Jamestown collection

- A severely burned horse tooth in the Jamestown collection

- A tiny glass bead from the fort’s second well

- Some of the faunal material from James Fort’s second well sorted by intern Lindsay Bliss

- Fish vertebrae that have been altered to create beads. These were found in the fort’s second well.

- Projectile point found in the burial fill.

- Groningen Token found north of the Church Tower.