Our archaeological excavations are focused on an area just south of the Archaearium. Work there began during the Field School and Kids Camps in the summer of this year. This area was part of a large burial ground that likely started being used in the 1610s. Starting in the 1660s a series of large brick buildings were built and rebuilt (due to fire) on the ridge where these colonists were interred and where the Archaearium now sits. This included Jamestown’s first purpose-built statehouse, famously torched by Nathaniel Bacon’s rebels in 1676. It’s in the context of these multiple uses (which also include centuries of farming after the capital was moved to Williamsburg in 1699) that the archaeologists are uncovering evidence of additional burials and 17th-century buildings.

A feature originally thought to be a cellar now appears to be a brick-lined grave. The bricks likely served as a foundation for a ledger stone which is no longer there. According to Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, English brick-lined burials didn’t come into use until around 1650, so this grave was one of the later ones in this burial ground. The construction of the statehouse and other government-related buildings in the 1660s, built on top of dozens of graves, gives a nice datable terminus to the burial ground. The archaeologists found a small builder’s trench surrounding the grave, allowing masons the access needed to lay the lower courses of brick.

The archaeological remains of a building that was initially thought to be contemporaneous with James Fort is now thought to date to the third quarter of the 17th century. The building’s footprint runs through several of the squares in the western part of the excavations south of the Archaearium. Its northern extent hasn’t been found yet, and the team is going to follow its footprint in that direction in an effort to define its bounds. The remains of this building cut through some of the graves here, indicating it was built after these colonists were interred. This clue made archaeologists reassess their earlier supposition that the building might date to the early 17th century. Because of the discovery of the building, the team opened up additional squares between the existing ones, in order to get a full picture of its archaeological remains. The team discovered burned timber inside one of these squares, the remains of which continues to the north. They’ll be investigating this as they move in that direction in the coming weeks. There were two fires at this location, the first in 1676 during Bacon’s Rebellion, and the second in 1698 that led to the relocation of the capital to Middle Plantation (present-day Williamsburg). Perhaps these timbers are evidence of one of those fires. Hopefully the excavations in the coming weeks will shed light on their date and function.

In the lab, Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe is mending an Essex Post-Medieval Blackware posset pot. Jo is continuing the work of Conservation Intern Jackie Bucklew who mended several sherds of the vessel during her time at Jamestown. Several additional sherds of the posset pot have been discovered in artifact storage in the Vault and so Jo is creating a stand for the vessel out of foam to support it during the mending process. Posset pots were used to pour posset, which in the early 17th century was a hot drink consisting of heated milk curdled by mixing it with wine or ale. Posset was thought to be a remedy for several common maladies. The sherds of this vessel were found in multiple fort-period contexts including the first and second wells and the blacksmith shop/bakery.

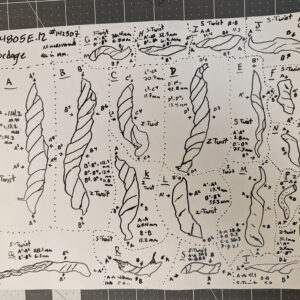

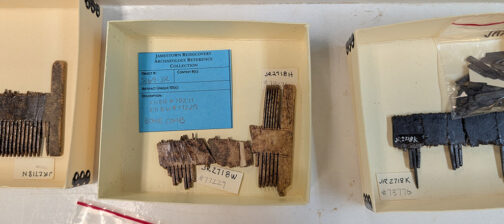

Just next to Jo, Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins is building storage containers for an assortment of cordage found in the Governor’s Well and the Smithfield Well. Most of the cordage was found in the Governor’s Well during excavations of its waterlogged layers in late September, 2023. Likely made out of hemp, the cordage would almost certainly not have survived had it not been submerged for the last 400 years, beyond the reach of the aerobic bacteria that preys on organics but that can’t survive underwater. A positive ID on the cordage’s composition should be in the works shortly thanks to the imminent arrival of a much-needed research microscope in December. Chris is building the boxes both to protect the artifacts and to permit more efficient storage because space is always at a premium in the Vault.

In the lab’s second floor Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown is photographing Chinese porcelain for an upcoming book to accompany an exhibit at Jamestown Settlement on the ceramic’s presence in the colony. The book, “Following the Dragon: Late Ming Porcelain from James Fort, Jamestown, Virginia” is researched and written by Merry Outlaw, Senior Curator at Jamestown, and is set to be published in 2025. The book will give insight into the manufacture of the vessels and how they came to be half a world away from their origin in China. For some vessels that are largely incomplete, Gabe will digitally overlay the sherds in the collection over more complete examples from private collections. This will allow the reader to see both the artifacts and the vessels as they were in the 17th century.

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp continues her work on bones found in James Fort’s first well, also called the “John Smith Well” because it was constructed in late 1608 or early 1609 while he was president of the council. Her count for bones of Layer “N” of the well is up to 82,000, up from 70,000 last month. This number may more than double by the time her work is complete. Dr. Elizabeth Reitz, zooarchaeologist and Professor Emerita from the Georgia Museum of Natural History visited Jamestown this month and lent her expertise to our curatorial staff. Dr. Reitz examined our iguana bones and deduced that we have two distinct iguanas in the collection. Iguanas are not native to Virginia. Captain John Smith and George Percy, both colonists from the original voyage to Jamestown, each mention killing iguanas while in the Caribbean:

In Mevis, Mona, and the Virgin Isles, we spent some time, where, with a lothsome beast like a Crocodil, called a Gwayn [iguana], Tortoises, Pellicans, Parrots, and fishes, we daily feasted.

The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles, John Smith, 1624

We also killed Guanas in fashion of a Serpent, and speckled like a Toade under the belly.

Observations by Master George Percy, 1607

For more information on the iguana bones in the collection and how they came to be identified please view Dig Deeper Episode 71.

The Southeastern Archaeological Conference (SEAC) was in Williamsburg this month and many of Jamestown’s archaeologists, conservators, and curators participated. Janene Johnston, Associate Curator at Jamestown, was a co-chair of the conference which hosted over 800 attendees. Jamestown staff gave 12 presentations in the program covering recent archaeological projects, collections-based research, conservation methodology, and public outreach. About 45 archaeologists attending the conference came to Jamestown for a behind-the-scenes guided tour of the excavations and collections area.

The Council of Virginia Archaeologists (COVA), Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources (DHR), the Archaeological Society of Virginia, and SEAC co-hosted COVA’s public day entitled “Celebrate Virginia Archaeology!” on November 16. Jamestown Rediscovery manned two tables at the event, one focusing on artifacts, allowing folks to pick through material excavated from James Fort’s first well, as can be done at the Ed Shed during warmer months. The other table, led by Director of Archaeology Sean Romo, was a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) exercise. Sean buried several objects in the sand and participants then used a handheld GPR machine to find and attempt to identify the objects using the data provided by the GPR. Over 30 organizations from across the state presented at the event and in excess of 1000 people were in attendance.

Several Jamestown Rediscovery staff members attended the annual Let Freedom Ring Foundation Gala, held at the Williamsburg Lodge on November 9th. This event supports the Let Freedom Ring Foundation and First Baptist Church, and their advocacy efforts for the African American descendant community in the region. Our team enjoyed meeting members of the descendant community, hearing speeches by Let Freedom Ring Foundation President Connie Harshaw and Martin Luther King, III, and a concert by Jonathan Butler.

related images

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid explains the Archaearium excavations to some visitors. Archaeological Field Technicians Eleanor Robb and Hannah Barch are at work behind her.

- The archaeology team at work south of the Archaearium

- The footprint of the brick-lined burial just south of the Archaearium

- A view of the burned timber found in excavations just south of the Archaearium

- Additional sherds of the Essex post-medieval blackware posset pot that will soon be mended by Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe. The circular piece is the vessel’s base.

- Cordage found in the Governor’s Well

- Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins created drawings of the various cordage found in the Governor’s Well. The measurements for each artifact record their dimensions while saturated, prior to any shrinkage that may occur over time as moisture escapes.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley gives a tour of the Archaearium excavations to Southeastern Archaeological Conference (SEAC) attendees.

- Senior Conservator Dan Gamble gives a tour of the lab to Southeastern Archaeological Conference (SEAC) attendees.

- James Fort as viewed from the pedestrian bridge crossing the Pitch and Tar Swamp

- Starlings visit Jamestown during their migration southwards.