A Kentucky team has used ground-penetrating radar to explore sites in Mexico, Italy, and across their own commonwealth. This month they took their own time to drive nine hours so they could explore the landscape around James Fort.

A Kentucky team has used ground-penetrating radar to explore sites in Mexico, Italy, and across their own commonwealth. This month they took their own time to drive nine hours so they could explore the landscape around James Fort.

George Crothers, director of the W.S. Webb Museum of Anthropology at the University of Kentucky, said the chance to explore Jamestown was compelling.

“Our program is proactive. We try to lead the way in the use of this equipment,” he said.

He and three others volunteered their time and equipment to survey land north and east of the fort for three days in the first week of November. They also looked at the foundations below the 1907 Memorial Church.

“It is a phenomenal, scientific practice. While we have used remote sensing in the past, it’s something that is always improving,” said David Givens, the Senior Staff Archaeologist at the Jamestown Rediscovery Project who worked to make the collaboration happen.

Dr. William M. Kelso, Director of the Jamestown Rediscovery Project said: “The work was a tremendous boon to the Jamestown Rediscovery staff, especially at this time as current excavations are suggesting that James Fort was much larger than the one-acre triangular fort so far explored. This advanced process for detecting archaeological features without digging can be instrumental in determining future excavation planning.”

The weather held for the surveys and was “the ideal condition. The soil makeup is great. The grass is perfect. This is the way we want it!” said Philip Mink, the Kentucky archaeologist who operated the ground-penetrating radar machine.

“Jamestown is one of those sites that everybody reads about in the popular press and in journals, and when I had the opportunity to come here and use my expertise in geophysical survey to help provide some information, it was something I jumped at right away.”

Their rolling ground-penetrating radar machine looked for objects within about 2 meters of the surface, and computer software then combines all the images to make a colorful 3-D scan of what the machine saw in the ground.

After Kelso saw one such scan, he said, “It’s fabulous. Seeing that image in 6-inch slices down through the ground, to about a depth of 6 feet, is fantastic.”

The radar results can seem overwhelming, Mink said. But it works well for what the team spends most of its time doing: quickly searching for forgotten cemeteries and significant historical sites in Kentucky in advance of road construction or other building projects.

“It’s good for solids like walls, bricks, floors,” Mink said.

The Kentucky team also used a magnetometer to measure magnetic fields within a meter of the surface of the ground. On their first day at Jamestown, they passed it over a 20 meter by 40 meter area just north of where the Jamestown Rediscovery team has been working this summer. They found a pipeline or an old power line; two iron poles buried in the ground as part of a system to protect a large tulip poplar from lightning, and some smaller features that may merit excavation. Additional processing of the raw data will help delineate those features from the more modern disturbances to the site.

While the ground-penetrating radar data will also be processed further, preliminary results indicate a possible path or old road, foundations, a well, and other features located both north and east of the present excavations.

“It’s always nice to have two different instruments because they will detect slightly different types of features, and then you can compare the two,” Crothers said.

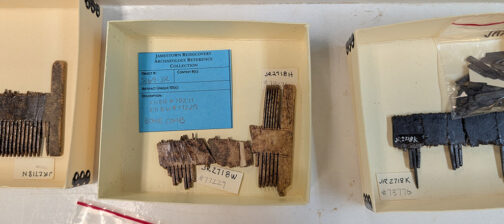

related images

- Kentucky ground-penetrating radar team at Jamestown

- Jamestown Rediscovery Archaeologist Dave Givens maps out the radar plan with Philip Mink

- Magnetometer exploring James Fort

- Philip Mink and George Crothers scan an open area north of the 1907 Memorial Church with ground-penetrating radar