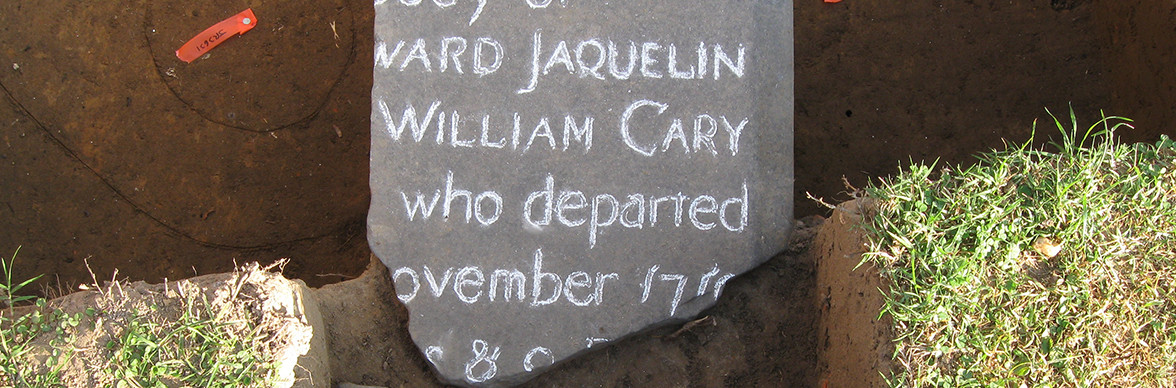

The headstone fragment doesn’t even have a woman’s name on it, but it may belong to a woman who was well-connected to important 18th century Jamestown history.

In the last week of September, the tombstone piece turned up as Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists dug on the east side of a brick wall attached to the gate to Preservation Virginia’s land. The fragment is from a tabletop (horizontal) gravestone that was in the graveyard outside the 1907 Memorial Church but is now separated from its burial site, probably as a result of vandalism during the 19th century.

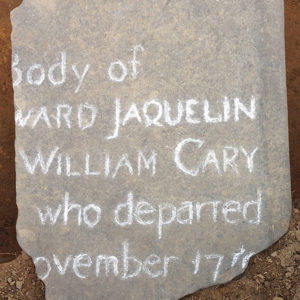

The fragment includes the words: “body of,” “ward Jaquelin,” “William Cary,” “who departed,” and “ovember 17??” Enough of the last two numerals of the date survive to strongly suggest they read “10,” or “13” but 1710 and 1713 don’t match the recorded death of the most likely candidate for the burial.

The date 1713 would match the father’s death year for that candidate. The only person who connects Edward Jaquelin and William Cary is Martha, who was born in 1686 to William Cary and Martha Scarsbrook Cary of Warwick County, Virginia, and then married Edward Jaquelin in 1706 or 1707. She died in 1738.

Taylor Stoermer, research historian at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, said burial stone language of the era could have produced this:

“[Here Lies ye] Body of

[MARTHA Wife of ED]WARD JAQUELIN

[daughter of Captain] WILLIAM CARY

[of Mulberry Island] who departed

[this life XX N]ovember 17XX

[Aged X year]s & X [months]”

Martha was Edward’s second wife. He was born in Kent, England, in 1668 and came to Virginia about the year 1697, acquiring William Sherwood’s land on Jamestown and marrying his widow, Rachel Sherwood. This made Edward Jaquelin the predominant landholder on Jamestown Island in the years immediately after the colonial government moved to Williamsburg in 1699.

After Rachel’s death, Edward married Martha. She gave birth to a son (Edward, in 1716) and three daughters: Mary, Elizabeth, and Martha Jaquelin. Elizabeth married Richard Ambler, Mary married John Smith of Shooter’s Hill in Middlesex County, Virginia, and Martha never married (but was a doting aunt; in one letter to her nephews studying in England in 1749, she lovingly chides John Ambler for taking her guinea coin and not repaying her one of his pleasing drawings).

Richard Ambler moved to Virginia from England in 1716 and settled in Yorktown because of property given to him by an uncle. It was his marriage to Elizabeth Jaquelin that drastically improved Ambler’s status and wealth. When Edward Jaquelin died in 1739, his property was turned over to Richard and Elizabeth Ambler and began the Amblers’ domination of the western end of the island for the next century.

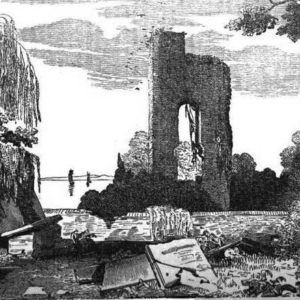

The ruins of an Ambler mansion stand today on Jamestown land owned by the National Park Service. Built sometime around 1750 along Back Street, 350 yards east of the church, the brick house was typical of early Georgian architecture. It had two stories, a central hall and two rooms on each side. The home burned during the American Revolution and was restored by Colonel John Ambler. The house burned again during the Civil War and was restored a second time. When the house burned for a third time in 1895 it was not rebuilt.

Likewise, the headstone of Edward Jaquelin has been lost to history. He was buried in the graveyard area outside the Jamestown church, but excavations by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities a century ago could not locate his burial.

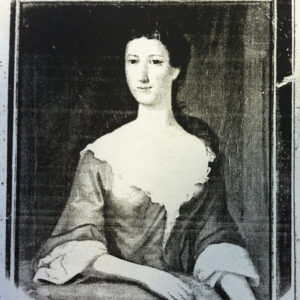

The traces of Martha Jaquelin are clearer. In addition to her newly-recovered headstone, there is a portrait of her at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, done about 1722 by Nehemiah Partridge. And she and her son gave to the Jamestown church a silver baptismal font in 1733-4. When the Jamestown church burned, it was returned to Col. John Ambler as the nearest representative of the donors. He presented it to Monumental Church in Richmond in 1831.

Martha Jaquelin was also the great-grandmother of Polly Ambler Marshall, who married John Marshall, the early chief justice of the US Supreme Court who established the court’s strength as an equal branch of government to the Congress and president. Another of Martha’s great-granddaughters was Polly’s older sister, Elizabeth Ambler Carrington, who has been honored by the Library of Virginia this year as one of its Virginia Women in History.

related images

- In the 1800s, vandalism of the churchyard was a problem. People would chip off pieces of headstones to take home as souvenirs.

- Martha Jaquelin portrait done about 1722 by Nehemiah Partridge and now at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

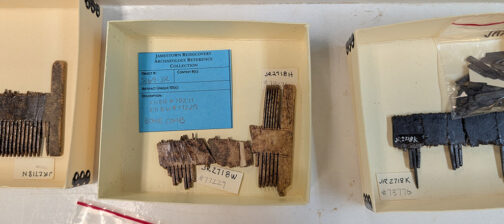

- Tombstone fragment found the last week of September