Could an oven inside the L-shaped cellar still bake bread today?

Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists working on the features were surprised this month to find that each oven had a roof largely intact. The oven along the east side of the cellar is giving archaeologists a really good look at its igloo-shaped interior.

“These are some of the most intact ovens we’ve ever excavated here at Jamestown,” said archaeologist Mary Anna Richardson.

“We’ve got a good deposit on the floor from during their usage. Excavating that occupation layer will be the payoff to help us answer that,” said Dr. William M. Kelso, head of archaeological research at Historic Jamestowne.

The investigation of these two features is informed by the 2007 discovery of two similarly-constructed bread ovens in a blacksmithshop/bakery cellar (Structure 183) near the north bulwark of the fort.

Jamestown Rediscovery Senior Staff Archaeologist Danny Schmidt said the two brick features now being excavated may be from an earlier time than the baking ovens found in 2007, which are believed to have been constructed ca. 1610-11 after the “Starving Time” winter and so were built larger than the two in the L-shaped cellar.

“Those ovens we looked at in 2007 were 95 percent collapsed. We saw just the edges of those,” Schmidt said. “These two now we could fire right up today.”

Finding an intact roof made this month’s excavation work a more delicate matter. Richardson switched direction and dug through the front of the oven on the southern wall instead of down through the top of that oven’s igloo-shaped cavity. Schmidt did the same on the eastern oven and found interesting details.

“The base of the oven is where a natural subsoil clay has been burnt to a brick consistency,” he said.

The two ovens in the L-shaped cellar were likely built in conjunction with each other. In addition to being about the same size, they also have a matching depth in the soil—the east one sits only three inches lower in the ground than the south one.

The bottom rectangle façade of bricks on the east oven is one brick thick and about 2.5 feet wide. Half bricks formed the arch façade around that oven’s cavity, and the spacing between the bottom rows of bricks and the framing arch indicates there was a wooden door about 2 inches thick on the oven.

Why a wooden door on an oven that could have been heated to hundreds of degrees? Kelso said the colonists could start a fire inside the oven with the door open, wait until the fire reached a certain temperature, then rake out the coals and place food inside with the door closed.

“It would stay hot a long time in there because it’s underground and in clay. It’s got a lot of insulation on it,” he said.

The bottom façade on the southern oven is thicker: a stairstep arrangement that is three bricks thick at its base. The southern oven may have needed repair: mortar neatly holds most of the bricks together, but on one side there is clay packed behind the façade bricks, as if the oven’s wall collapsed and needed reinforcing and there was no more mortar to use.

Kelso is also curious about scorch marks on the wall to the right of each of the ovens and near the floor of the cellar. That pattern indicates something about the ovens’ use, he said.

“This cellar is a great argument for context, as opposed to just digging holes in the ground,” Kelso said. “Our slogan is: It’s not what we find, it’s what we find out. In archaeology, you really want to find a time capsule layer like we have with the floor of this cellar. And then we do the CSI thing. We are trying to reconstruct an event.”

The cellar being explored now is 25 feet long and dates to the early James Fort period (1607-1610). This cellar aligns with James Fort’s first well, which sits 10 feet away to the west and at the same angle.

related images

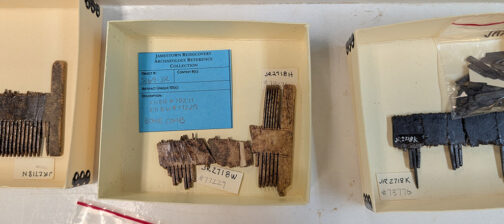

- Jamestown Rediscovery project archaeologist Mary Anna Richardson explored the dome of the brick oven on the southern wall of the cellar

- Jamestown Rediscovery senior staff archaeologist Danny Schmidt works on the dome of the brick oven on the eastern wall of the L-shaped cellar.