June brought the opening of the 2016 Jamestown Rediscovery Field School and the opportunity to investigate areas adjacent to the north side of the 1907 Memorial Church. Fourteen students from all across the country spent six weeks with our staff learning archaeological field methods, 17th-century material culture, and conservation techniques. Students who completed field school earned six credits in Anthropology from the University of Virginia, and they are now qualified to volunteer in Jamestown Rediscovery’s excavations.

Digging along the exterior of the Memorial Church’s north wall, the team anticipated gaining new insights about the three colonial churches constructed on the site, beginning with the first, built in 1617 during Captain Samuel Argall’s term as governor. Because the first church in this location was built just ten years after English occupation, archaeologists hypothesized that the native horizon would be intact, and therefore would reveal evidence of Virginia Indians. As well, it was thought that evidence of the 1608 palisade expansion that occurred during Captain John Smith’s leadership might be revealed.

After establishing grid squares, students removed topsoil and a one-foot thick layer of brick, mortar, and plaster rubble in the churchyard during the first two weeks. The topsoil was filled with evidence of 20th century landscaping and rubble from repairs of the Memorial Church’s slate roof. It yielded spare change from the 1970s and ‘80s, flash bulbs, assorted plastic litter, and a Kate Spade purse tag. Two of the test units contained planting holes, probably dug after construction of the Memorial Church. The foot-thick brick, mortar, and plaster fill resulted from early-20th-century excavations and later landscaping activities in the north churchyard. Interestingly, there were three tools found in this layer that were likely used in the Memorial Church construction–a carpenter’s framing square and two drawing compasses!

Soon after Mr. & Mrs. Edward Barney gifted 22.5 acres of Jamestown Island to the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) in 1893, a couple of the organization’s founders began the task of preserving the property’s most significant site: the Jamestown church tower and church foundations. Members began by removing the vegetation from the ruins and cemetery, and then by trenching around the church foundations. APVA founders Mary Jeffery Galt and Mrs. Park C. Bagby described their initial impressions of Jamestown as “a picture of desolation.” Galt remarked, “It seemed a wilderness of poor deserted farm land.”

In her Jamestown report to Mrs. John B. Lightfoot, Galt shared some details of the excavations she participated in with Richmond stone mason William Leal, Army Corp. engineer John Tyler, Mary Garrett, and Annie Galt. She reported that in 1897, she dug with her own hands inside the foundation of the church’s south wall and discovered a small “inner wall composed of a layer of bricks and cobblestones,” which she surmised belonged to the 1617 church. Galt also mentioned finding tombstones broken up by vandals, and she noted that the fragments were reburied to protect them. Photographs taken after the 19th-century excavations show that barbed wire fences and a wooden barn structure had been built around the church ruins by the APVA to protect the site from trespassers and vandals. Galt’s only mention of the area we investigated this summer was that broken glass and masses of brick and mortar were found in this location. She theorized that the north wall of the 1680s church was partially intact when a strong wind caused it to fall outward. Partial clearing of the area is shown in a 1901 photograph taken from the tower looking down at the church’s brick foundations. As previously noted, our current excavations revealed that much of the rubble described by Galt was cleared in the 20th century during landscaping activities around the church.

In spite of a few 20th-century disturbances, senior staff archaeologist Dave Givens noted that a great deal of information can be gleaned from the mixed brick, mortar, and plaster rubble excavated during field school. Givens said, “We’re finding that there are two different types of interior plaster. One type was backed with lath and probably related to the timber-framed church built in 1617. The second type showed impressions of brick and likely relates to one of the later churches.”

Once the overburden was cleared, it was evident that the prehistoric layer was reasonably intact close to the church as predicted, but that it decreased in thickness as we moved farther from the building. The prehistoric layer was surprisingly devoid of features. By the end of June, staff and students had identified six burials, and determined most of the postholes uncovered were from the late-19th century fence erected by the APVA to secure the church site. Also, during the last two days of June, elongated, parallel dark black stains, approximately one foot wide, and perpendicular to the church foundation began to appear. These are believed to be remnants of the colonists’ first planting rows located just outside 1607 James Fort’s east palisade wall. More results of the excavation will appear in the July Update, so stay tuned.

Finally, every field school participant had the opportunity to excavate the cellar well in building located in the Palisade Extension, Structure 193. See our Dig Update video featuring senior staff archaeologist Danny Schmidt for some of our most recent discoveries in the well!

related images

- Aerial view of the site on the first day of the Jamestown Field School excavations. Units are north of the Memorial Church.

- Aerial view of the cellar site and the new test units on the north side of the Memorial Church.

- Photo taken in the churchyard looking toward the tower around the time that the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities acquired the property and began excavations around the church foundations. (Photo Courtesy of the Valentine Museum, Richmond, VA.)

- Jamestown church foundations during the 1901 excavations by members of the APVA. (Photo Courtesy of the Valentine Museum, Richmond, VA.)

- A drone hovers over the site capturing photos of the first couple of days of progress.

- Students pause to examine a brick wall that was built in the late 18th or early 19th century by Mr. John Ambler of Jamestown Island and Mr. William Lee of Greensprings. These gentlemen’s family were still using the cemetery at this time although the church was out of use in the 1750s.

- Reverse of a Spanish half-real cob minted in Mexico was found in the overburden near the Memorial Church

- Ornate brick found in the brick rubble layer which might have been used as the base to a column in one of the brick churches built on the site.

- Student Michelle Carpenter exposes more of the Ambler brick wall which surrounded the cemetery in the early 18th century.

- Student Hannah Richardson holds a fragment from a spur found in one of the test units.

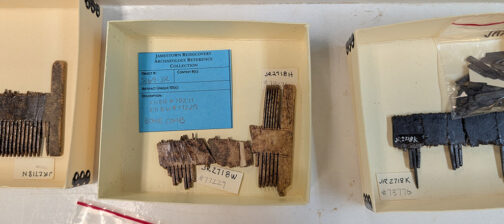

- Pieces of ivory comb found in the overburden of one of the test units near the Memorial Church.

- Students Sarah Harris (left) and Sarah Iler (right) wash some of the artifacts that their groups have uncovered in the field during their lab day.

- Student Becca Merriman-Goldring talks about a carpenter’s framing square that her group found at the site. The square may have been used by those constructing the Memorial Church in 1905-1907.

- Senior staff Archaeologist Dave Givens shows students Michael Stanford and Shannon Long some of the butcher marks on a large cow bone found in the overburden north of the church.

- Most of a Morrow Mountain projectile point found at the site. Dated to the Middle Archaic period.

- A child’s molar with filling that could be as recent as the 1970s.

- Students Emily Bender and Hannah Richardson draw a plan view of the half unit excavated near the Jamestown church tower.

- Student Amy Baker records the west profile of a test unit. The three layers visible are topsoil, brick and mortar rubble archaeological till and native top soil from the 17th century.

- Plaster samples in the lab dry after being washed by the students.

- The first trowel cleaning of the site by the group.