A team of Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists is excavating the 1680s Church Tower, the last above-ground structure that still exists from the 17th century. Led by Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, the goals of the excavations are manifold. A glass floor will soon be installed, allowing visitors to enter the Tower and examine the archaeological resources beneath their feet. Typically the team backfills excavations, but these will be left open for that purpose. Lights will be installed to illuminate the archaeological features and a fan will be installed to prevent mold growth. Visitors will be able to see a variety of features through the glass floor. The original 1607 eastern palisade wall goes right through the Church Tower footprint. A large burned section of earth that almost fills the entire area of the Church Tower is likely the remains of the wood-framed church belfry that was put to the torch by Nathaniel Bacon’s rebels in 1676. Foundations of the western end of the 1617 church are clearly visible in the middle of the Tower’s footprint (Learn more about the discovery of the foundations here.). This was the first church in this space and was the location of the first representative governing body in the Americas, the General Assembly of Virginia, a legislative body that still meets to this day. Finally the team is very interested in excavating the builders trench of the Church Tower itself, hoping to find a diagnostic feature or artifact that will help them more precisely date the structure. Although we are confident that it was built in the fourth quarter of the 17th century after the wooden belfry was burned down, we haven’t yet been able to pinpoint the construction timespan via archaeological evidence. As has been the case with other buildings at Jamestown, hopefully someone dropped something in the builders trench during the Tower’s construction that will help date it.

The team is in the process of excavating two of the corners of the builders trench inside the Church Tower. Director of Archaeology David Givens noted that the masonry on the Tower below the ground is well done, with nice level lines of bricks and remarkably neat joints, the work of a skilled mason. Lead scrap and a case bottle neck have been found in one of the corners so far. There’s still quite a lot of archaeology to go in the Church Tower. February should be an exciting month for the excavations here.

In the excavation structure adjacent to the ticketing tent visitors can get an up-close view of archaeology in action on the edge of the churchyard. The structure looks and acts much like a greenhouse, keeping the archaeologists warm during the winter months. Last fall it was used to enclose the burial excavations of three colonists who died during the first year of the settlement at the western edge of James Fort. The team continues to delicately scrape away at a large posthole or pit which has only partially been exposed, as yet hiding its dimensions. Several features just inside the western edge of the structure have been positively identified as burials which makes sense given the structure’s proximity to the Church. One of the goals of the dig here is to give definition to the boundaries of the churchyard and also to a section of the Great Road, which should pass close to here on its way to the banks of the James River. A projectile point found here this month could possibly be a Clovis point, as old as 12,000 to 13,000 years. It is unfinished, possibly broken and discarded during production.

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) was used extensively in January, primarily in two locations. The first, in the marsh north of James Fort, was another experiment to see how effective GPR could be in saturated areas. While thorough analyzation of the results has yet to be completed, typically saturated runs result in very limited data. High amplitude features — that is those that strongly reflect the radar signals being emitted by the GPR device — may still be detectable. An area of 100 feet by 265 feet was surveyed with the GPR machine in this marshy area. This part of the property was dry when the project began 30 years ago and small-scale archaeological excavations were conducted here in the 1930s. The GPR surveys are one way of attempting to discover what we’ve lost or stand to lose as the swamp continues to rise and claim more of the island.

GPR surveys were also conducted just outside the northwest corner of James Fort. The area is largely comprised of Confederate Fort Pocahontas‘ earthworks but was once adjacent to the “two fair rows of houses” built in the 1610s. The area is full of objects that can obscure the GPR data, including the remains of trees, a borrow pit used by the Confederates and their enslaved workers to mine soil for the construction of Fort Pocahontas, and even screened dirt from earlier archaeological excavations in the first decade of the 2000s. The team is intrigued by some of the data and are planning future shovel-in-ground investigations to flesh out anomalies discovered by the GPR. There is no timeline for these future excavations as of yet.

A huge event in the history of the 1680s Church Tower took place on January 29. Steel infrastructure was installed inside the Tower, just below the top, to support a glass roof. The Tower has been without a roof for over two centuries and the lower-fired bricks inside, never meant to be exposed to the elements, have degraded as a result. The roof, complete with gutters to divert water away from the 350-year-old structure, will protect the Tower’s interior and allow the installation of a glass floor permitting views of the archaeological resources below. The roof was a local effort, with support from Stemann | Pease Architecture, Daniel & Company, and Metal Masters. A crane was needed to lift the steel structure into the Tower and the weight of the crane presented challenges due to the underground archaeological features on the path to the Church. Heavy duty pallets were put in place and the crane drove over these to distribute its massive weight over a wide area and prevent damage to the archaeological resources. Two men stood in the Tower and helped guide the steel structure in place with nary a scratch to the historic bricks. Next up is the installation of the glass panels themselves, due to arrive shortly. The roof will be invisible from the outside, maintaining the Tower’s iconic look. You can watch recordings of the roof installation from two angles on the Church Tower page.

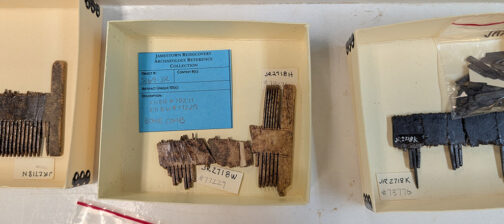

The collections team was happy to have Princeton University student Alex Heine work with them in January. Alex helped pick through small finds found in James Fort’s first well, identifying and separating beads, animal bones, charred wood, and lead shot. He also worked with Senior Curator Leah on Jamestown’s knives. Alex measured each knife, replaced handwritten tags with printed ones, and bagged all knives that aren’t part of the Reference Collection. There are two main types of knives in the collection, whittle tang, and scale tang. The whittle tang knife has its tang (the part of the blade that extends into the handle) totally encased in the handle. A scale tang knife is one which tang is covered by a multiple piece handle, joined together by screws or rivets. Some scale tang knives are clasp knifes, a form similar to modern Swiss Army knife, in which the blade rotates in and out of the handle. Many knives are found in two parts, with the iron blade and tang separate from the bone handle. Knives that are found intact, with both the blade and handle together are occasionally separated into the two components during the conservation process. The conservation method(s) for the metal blade may be incompatible or even detrimental to the handle and vice-versa. During the process of taking some of the knives apart, Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins has noted the smell of resin, a centuries-old aromatic time capsule of the adhesive used to keep the handle attached to the blade.

The identifications for, organization of, and database editing for Jamestown collection of projectile points is complete! The reference collection is nearing completion, with website content in progress. Over 1,200 points have been excavated by the team since the dig began in 1994. The collections team has produced several new webpages showcasing examples of the projectile points in the collection, including a MacCorkle Projectile Point dating from 6900-6700 BCE, and small triangular points, the type in use when the English arrived, that date from 1400-1700 CE.

Though the Archaeological Field School is months away, the collections team is gathering its collection of delft tiles for mending by the students. The collections consists of hundreds of sherds and some fairly complete examples. We are interested in making the tiles more complete to learn what the illustrations on the tiles depict, and then conduct further research on those illustrations and how the tiles came to Jamestown. These tiles would have been made in the Netherlands and many of them are adorned with “ram’s head” motifs in the corners. You can read about one of the more complete examples, a man with a cart of apples, on the Delft Tile webpage.

Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens and Conservator Don Warmke have been working on mending a new sherd found in the artifact vault to a Bartmann jug that was on display in the Archaearium. While thrilled to be able to make the artifact more complete, the task is a daunting one since the sherd fits into a space on the Bartmann not accessible without removing already-mended pieces. Chris and Lauren have to remove the reversible adhesive to disassemble the section, add the new piece, and then put everything back together before installing it back in its exhibit. The task is made more difficult by the fact that the jug is missing its base and so a temporary foam mount is being used to give it support during the process.

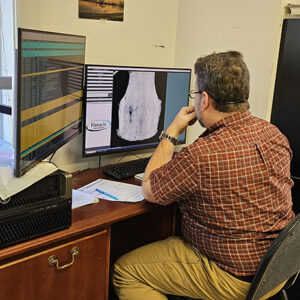

The conservation team is removing one of the breastplates from the Archaearium for additional conservation. The breastplate, constructed perhaps as early as the 15th century, showed signs of corrosion during a routine inspection of the artifacts in the museum. Before conservation occurs, the team will X-ray the breastplate, looking for any weak spots that they need to take special care with during the conservation process. The breastplate will first go into an acetone bath to remove the Syncralac coating that currently helps protect the artifact from corrosion. Senior Conservator Dan Gamble will then bring it into the air abrasion room where he will carefully remove the active corrosion areas. The breastplate will then be placed in a sodium hydroxide bath for several weeks, which leaches the chlorides out of the artifact. Chlorides are contributors to the corrosion process and this bath acts to remove as many of them as possible. Once out of the bath, the breastplate will be coated with Paraloid B-72, which has been shown to be a superior preventative coating to Syncralac for iron.

Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins has conducted Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) on several jet artifacts in the collection. The process uses a short laser burst to create a plasma that is analyzed to determine the chemical makeup of the object. Among the objects Chris processed were a bead, a jewelry setting, and several crucifixes. The data will be sent to Dr. Richard Hark of Yale University for analysis. We’re hoping the process will pinpoint where the jet came from, the two likely regions being Whitby, England, and Asturias, Spain. Crucifixes similar to those in the Jamestown collection have been found in Whitby.

Chris is also conserving leather found in the Governor’s Well. Among the leather found in the well are several shoe soles. Chris is using ethylenediamine tetracetic acid (EDTA) to remove the iron salts and then applying a glycerol treatment as a bulking material to replace the leached salts and prevent shrinkage and cracking. He is now slowly air drying the pieces beneath layers of plastic and regularly checking in on the progress. Some shrinkage is inevitable but Chris is doing everything possible to minimize it. Because the leather will shrink to some extent, Chris did tracings of the objects on transparency sheets to record their dimensions prior to starting the conservation process.

related images

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis excavate plaster found in the Church Tower excavations.

- A case bottle neck found during the Church Tower excavations

- The archaeological team discusses the excavations east of the Memorial Church inside the former burial tent. The greenhouse effect of the tent allows the team to excavate on days when it would otherwise be too cold.

- Curator Janene Johnston holds a possible Clovis point found in the excavations in the former burial tent.

- A lead shot found in the excavations east of the Memorial Church inside the former burial tent.

- Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown, Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo, and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid (L-R) lay out the grid for the GPR survey to the west of James Fort’s north bulwark.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch conduct a GPR survey of the area just west of James Fort’s north bulwark.

- The crane used to lift the Church Tower’s roof infrastructure drove over heavy duty pallets to avoid damaging the underground archaeological resources.

- The steel roof infrastructure in place inside the Church Tower, January 29, 2024.

- Lowering the steel roof infrastructure inside the Church Tower

- Two workers carefully guide the steel roof infrastructure inside the Church Tower.

- Lowering the steel roof infrastructure into the Church Tower. The heavy duty pallets that the crane traversed to get to its location can be seen at left. The pallets distributed the crane’s weight to protect the archaeological resources along the path.

- The Jamestown Rediscovery projectile point collection. Examples range from thousands of years old to the 1600s.

- Some of the bone handled knives in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection. Reference collection examples are situated at the front of the tray.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds an example of a scale tang knife. The rivet holes to attach the handle to the tang are readily apparent.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds a bone handle for a whittle tang knife.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds a bone handle for a whittle tang knife.

- The breastplate in the Archaearium before undergoing additional conservation.

- Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins examines a new X-ray of the breastplate taken out of the Archaearium for conservation. X-rays help inform the course of conservation by showing the density of the metal across the entirety of the artifact. A thin portion may mean extra care is taken in that area or that a different course of conservation is used to avoid damaging what’s left of the original metal.