With winter in full swing the archaeological team has moved indoors to focus on analyzing, conserving, and cataloging artifacts. One of their primary focuses is the Angela site, the location where Angela, one of the first Africans forcibly brought to Virginia in 1619, is known to have lived in 1620s. The collections team continues their work conserving and cataloging artifacts as well, with a featured project this month being a 17th-century cauldron not from Jamestown but from Bacon’s Castle across the river. Our botanical collection is now in much better shape due to the efforts of Curator Leah Stricker who spent much of last year organizing, cataloging, and reevaluating the conservation of many of our plant-related artifacts.

Though cold temperatures have driven the archaeologists from the field, they have turned their efforts towards processing artifacts from the Angela site, where Angela worked in bondage for Captain William Pierce in the “New Towne” section of Jamestown. Between 2017 and 2020, in partnership with the National Park Service upon which land the site sits, the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists conducted excavations there in the hope of learning more about Angela and her world. The enormous quantity of artifacts recovered from the site has meant that the processing of them will take several years.

Dr. Chris Wilkins of the conservation team is working on a cauldron found at Bacon’s Castle, a 17th-century plantation across the James River in Surry County. Built in 1665, the main house is one of only three Jacobean “great houses” that still survive in the New World. When Nathaniel Bacon’s men approached the property and forced Major Arthur Allen II to flee his plantation during Bacon’s Rebellion, they helped themselves to the food and drink found there. The cauldron that Chris is working on was found in a pit feature in the mid-1980s that is thought to have been a dumping ground during the cleanup following the rebellion. A wealth of artifacts were found in the pit, including wine bottles, animal bones (food remains), and this cauldron.

Preservation Virginia, the owners of Bacon’s Castle, have asked the Historic Jamestowne conservation team to conserve the cauldron so that it may go on display at the Castle. Chris is taking a multi-faceted approach to the conservation by using a variety of tools and chemicals to stabilize the cauldron, the methodologies used being typical for most iron artifacts. One of these tools is an air scribe, which Chris describes as a tiny jackhammer, to remove thick concretions — mixtures of rust and soil — covering the cauldron. For thinner sections of overburden he uses an air abrader, a device that spits out a fine stream of aluminum oxide particles in a process also used in the dentist’s office. Showing how the science of conservation evolves, Chris is also removing microcrystalline wax, a preservative treatment by an earlier conservator. The substance can actually trap moisture against artifacts and so is out of favor with conservators today.

Once Chris has completed the overburden removal, he will soak the cauldron in at least two baths of sodium hydroxide to cause any chlorides in the iron to leach out. The removal of chlorides helps inhibit any future corrosion. Finally, the object will be coated in tannic acid, which reacts with the iron to form a protective barrier to help prevent corrosion. Then the cauldron will be placed in an oven to remove moisture from the tannic acid coating. A coating of B-72 is then applied to prevent oxygen from reaching the metal surface. Generous donations to the Merry Outlaw Curatorial and Conservation Fund help provide lab equipment and chemical solutions which enable us to protect and preserve these priceless artifacts.

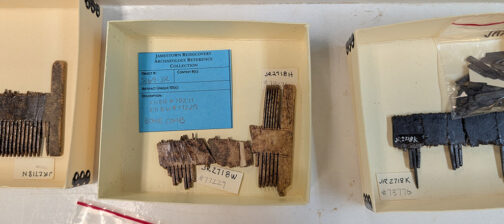

Curator Leah Stricker recently presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology (SHA) conference on her project to conserve and curate portions of the botanical collection at Historic Jamestowne. Since the project’s beginning in 1994, thousands of botanical artifacts have been found, from large wooden planks lining fort-period wells to the tiniest tobacco seeds found submerged in their depths. Thanks to funding from the Skiffes Creek Curation and Conservation Research Plan, Leah has been able to better curate many of our botanical artifacts, reevaluating the best long-term conservation and storage methods for them. Enhanced cataloging using our database software will allow subsequent researchers to have more information at their fingertips, and Leah has consolidated much of our botanical collection into a single, easily accessible cabinet in the vault. Some of the artifacts that have benefitted from the project include a wooden-handled hammer, walnuts, leaves, pumpkin/squash seeds, and a Roman lock pistol now on display in the Archaearium.