Behind the Scenes of Illustrating the 2024 Burial Excavations

February 27, 2025. Eleanor Robb, Archaeological Field Technician.

Every year, the field crew at Jamestown Rediscovery excavates three burials from the 1607 burial ground inside the fort, which contains approximately 36 graves from the first year of English settlement. For the past several years, the team has built a structure over this excavation area, not only to keep the human remains within safe from the elements, but also to keep them out of the view of the public during such sensitive excavations. Jamestown Rediscovery has also become increasingly selective about sharing photographs of these human remains on public platforms. This decision has been made partially out of respect for visitors who may find these photographs unsettling to view. Jamestown Rediscovery also strives to treat the human remains excavated here with the respect and dignity they deserve. After all, these were actual people who lived and died here. This means that we keep our burial excavations out of the public eye, both on site and online. As a public archaeology site, however, we strive to keep our visitors in the loop with everything we learn through our excavations. So, how can we present our findings during burial excavations in a respectful manner without sharing photographs? The answer lies in illustration.

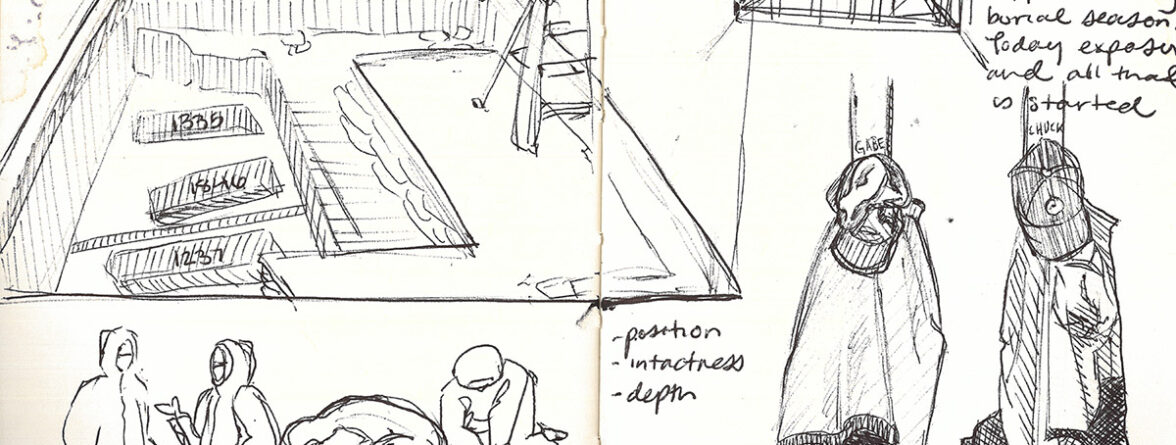

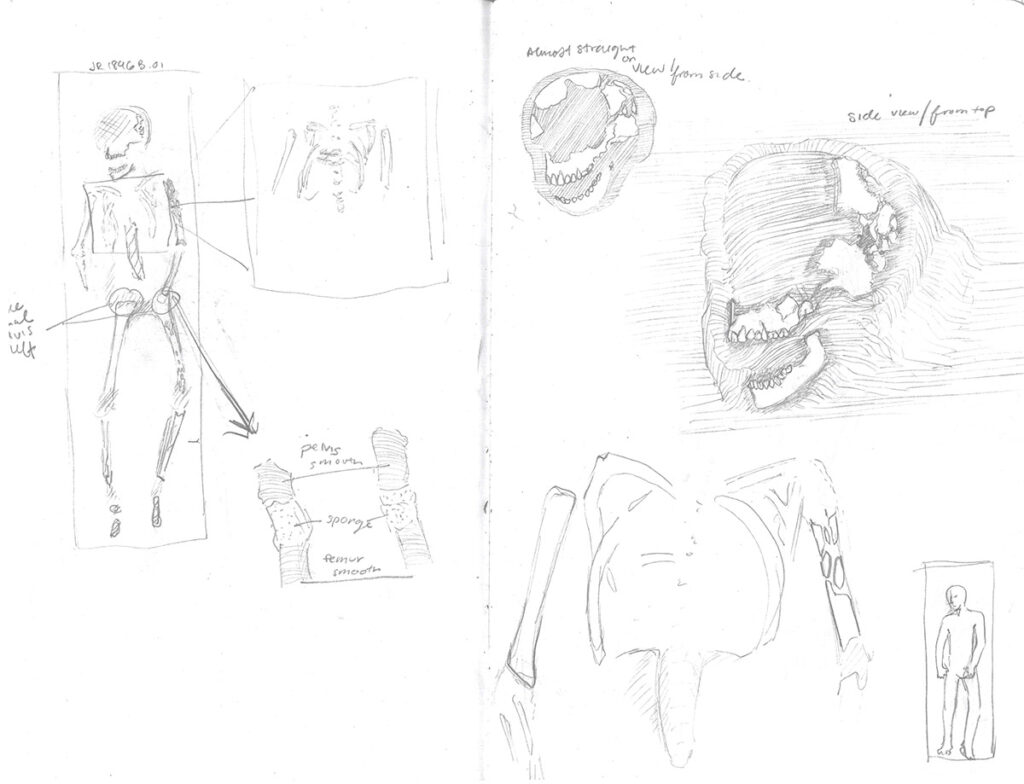

Archaeological illustration is used regularly at all stages of excavation, especially when recording the stratigraphy of the site. Conservation staff also regularly draw artifacts in order to better study them and make their elements easier to identify. The illustrations I made of the burials this year combine these efforts by representing and recording the excavation area, the remains we excavated, and the methods we use. The production of three illustrations for the burials at the 1607 burial ground began early in the excavation process. As a newer member of the crew, I did not participate hands-on with most of the excavation of human remains this year. Instead, I orbited between burials, supporting the team’s work while also closely observing the excavations and making live sketches of the human remains, of the archaeologists, and of the whole excavation area. These live sketches allowed me to take very detailed notes of the positioning and condition of the human remains without relying on a two-dimensional photograph and the limitations of its quality.

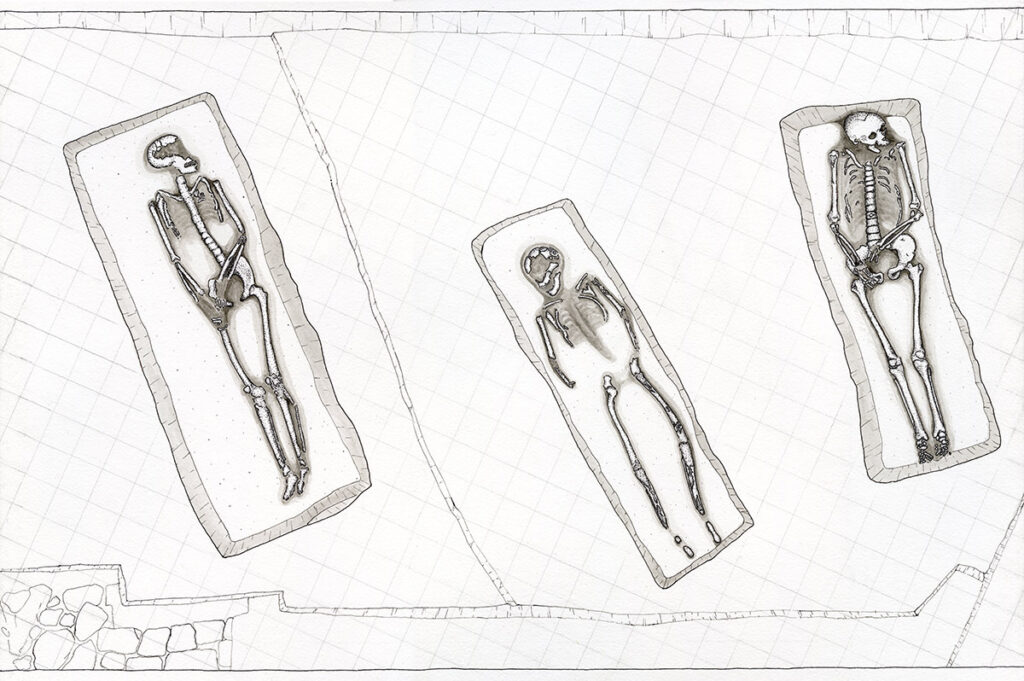

Click to enlarge images. Live sketch and notes on burials JR1237, JR1846, and JR1335, after the remains were exposed in situ.

After the excavations were complete, I consulted with Director of Archaeology Sean Romo and Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley to decide what kinds of illustrations would be most useful and appropriate to produce. Three different types of images were chosen: two overhead illustrations of the whole burial site, one in watercolor and one in pen and ink, and one painting adapted from one of my live sketches which would show two of our archaeologists at work.

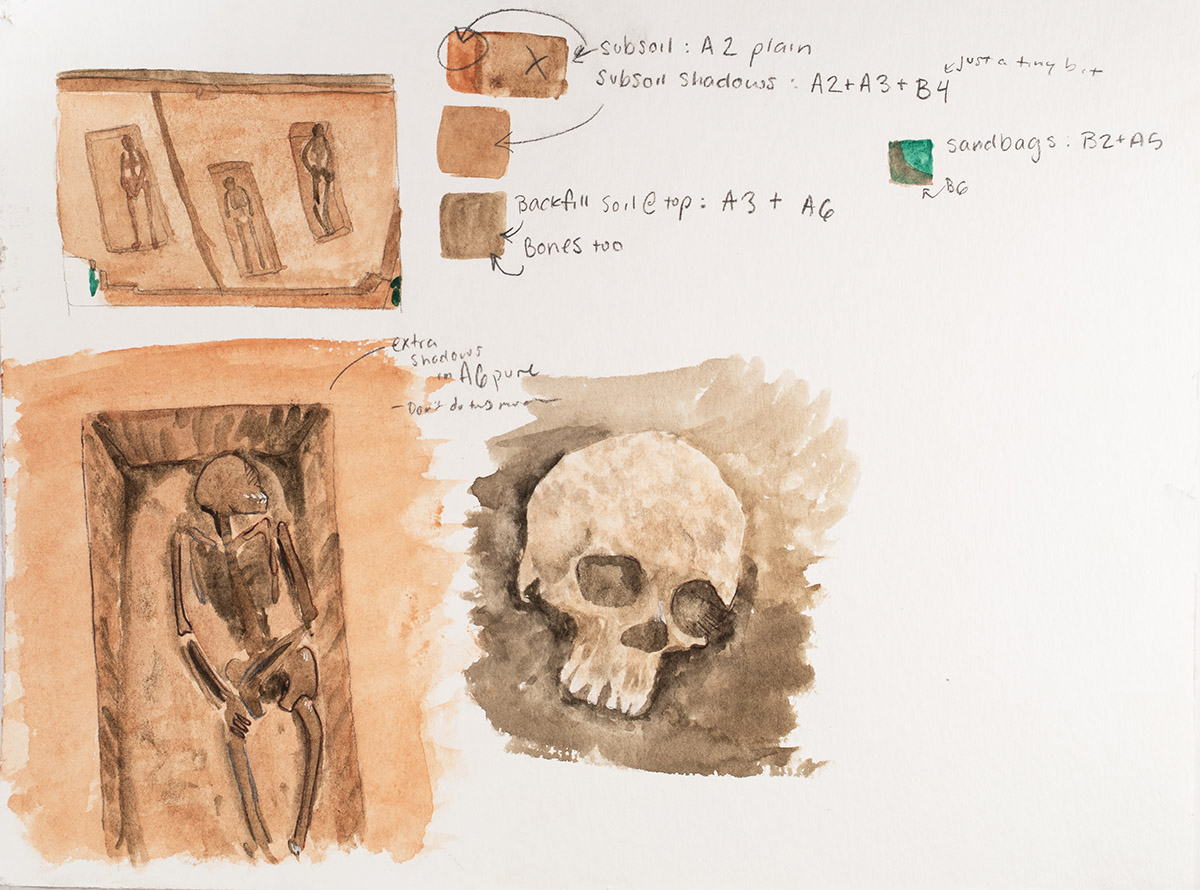

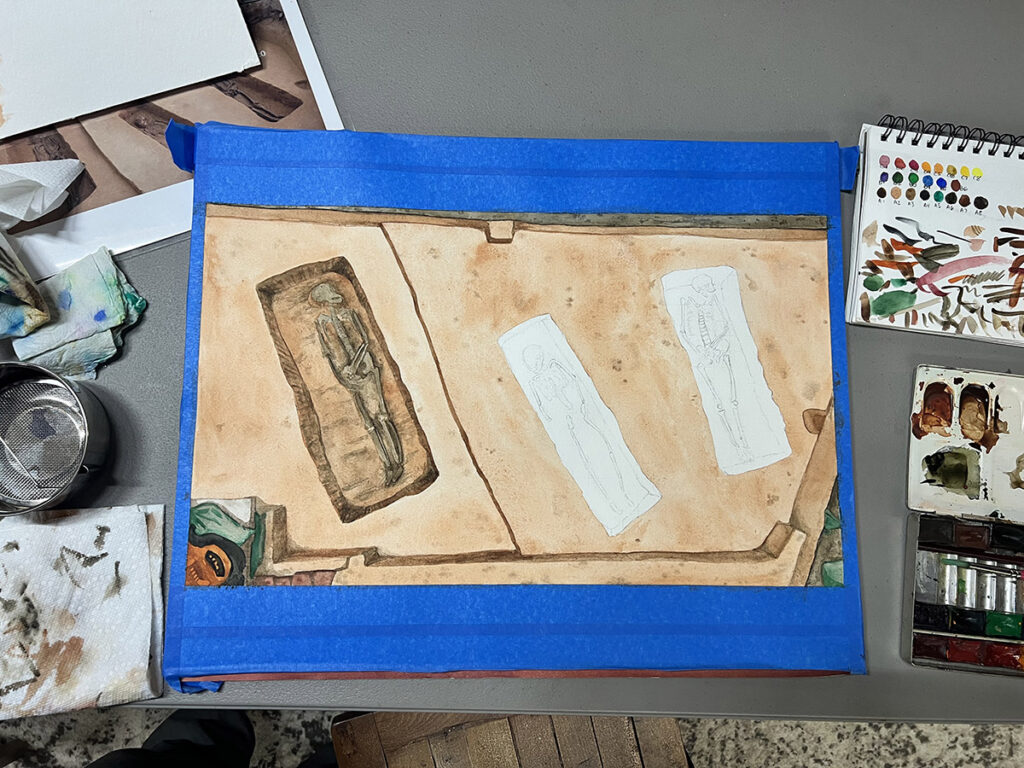

Each illustration also required different kinds of preparation in order to achieve the desired effect. For the watercolor paintings, I used a test sheet to determine how to mix each color I needed to use. I painted a swatch on the sheet and labeled each with what paints I used to mix it. Additionally, I painted a small test of the sets of remains so that I could see how all the colors would work together in the final product, and made notes about my process during this stage. This “cheat sheet” was helpful in maintaining a consistent result in both paintings over the multiple days that they were in progress.

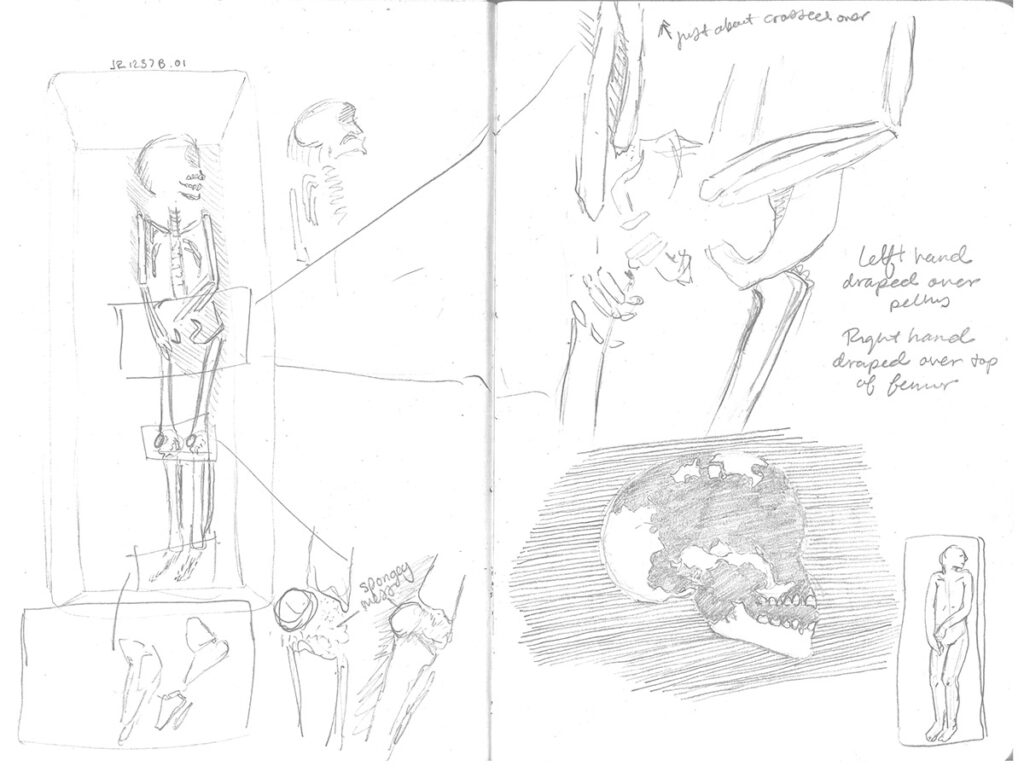

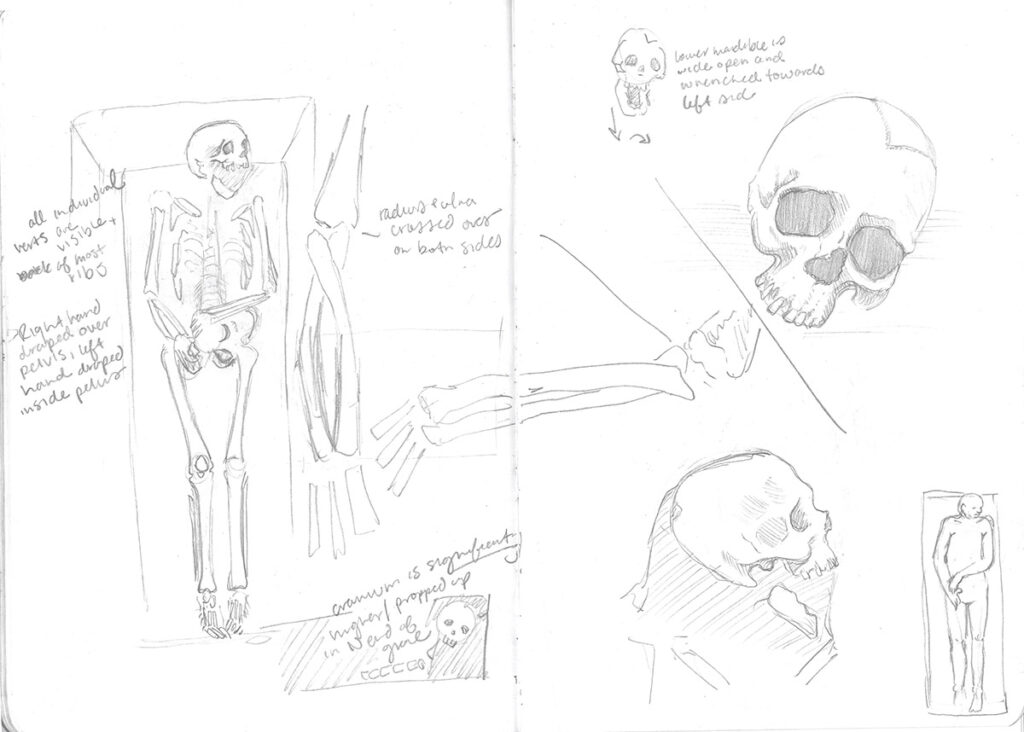

For my pen and ink illustration, I created another test sheet by drawing the outline of one of the burials four times over, and using eight different shading techniques across them. This enabled me to consult with other staff members, especially with Director of the Archaearium Jamie May, as to which method would be both the most visually appealing and convey the most information about the remains. Jamie’s insights were particularly valuable, as she is not only an archaeologist with decades of experience, but an expert archaeological illustrator as well.

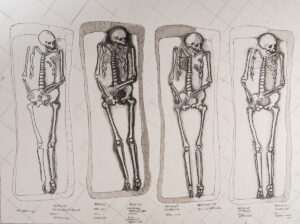

(L) The large painting of all three burials in progress (R) Putting the final touches on the large pen and ink drawing

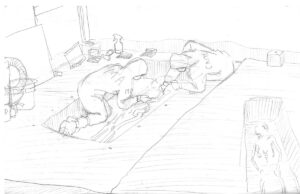

Finally, for both the painted and inked overhead compositions, I overlaid a grid across my reference image, drew the same grid on my paper, and transferred the necessary lines. Then I was able to use my “cheat sheets” to create the final illustrations, making adjustments where needed. For the painting depicting the excavations in-progress, I recreated my sketch on a larger scale, and added color to create a lifelike scene.

Each piece serves a specific purpose. The watercolor painting of all three excavated individuals provides visual information comparable to what our final record photograph would provide. In full color, the remains are situated within the excavation area, including other archaeological features in the area as well as elements of the excavation structure. This painting strikes a balance between the accurate and the artistic. While all of the elements in view are accurately positioned, the painting is a step away from the minute detail of a photograph or a penned drawing, and it wouldn’t be possible or accurate to take measurements from a painting like this.

The pen and ink drawing gives a more technical view of the remains as archaeological finds. This drawing includes a 0.5 foot grid spacing in pencil, which is not only to scale with the remains represented, but is also oriented with the archaeological grid upon which all of our excavations are based. This means that this drawing is useful for more specific purposes, such as reports or presentations, and can be used to take quick or approximate measurements of the burials.

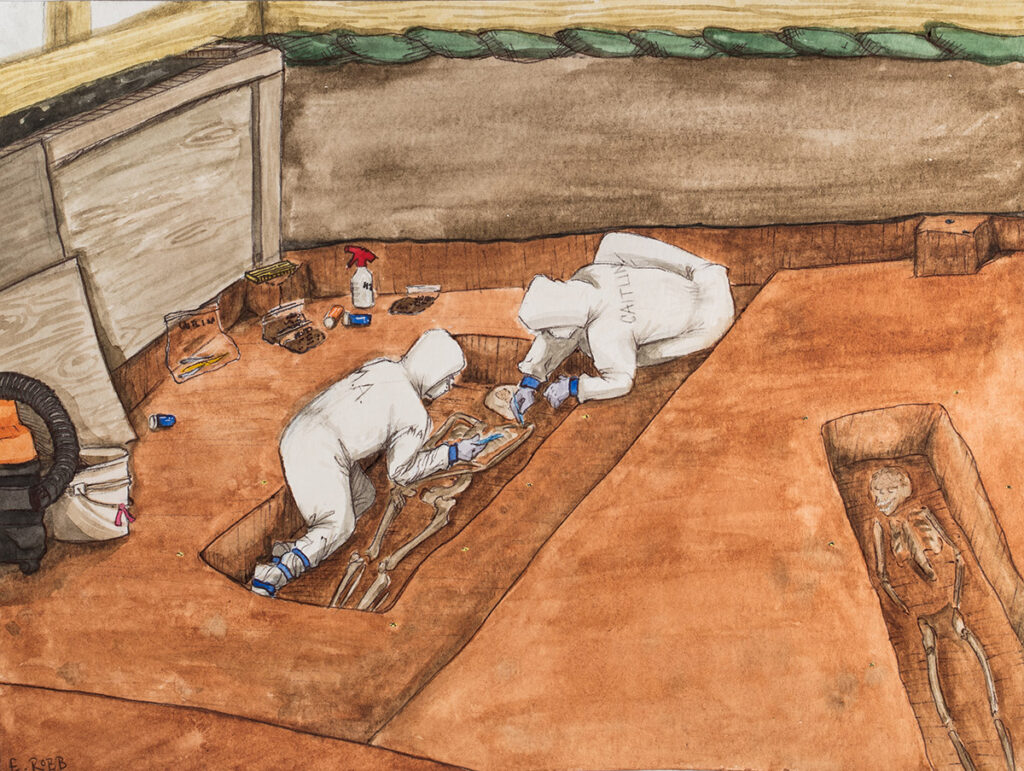

The working scene, another watercolor painting, is less accurate than the other two illustrations, because it is based off of a live sketch. Rather than conveying information about the remains themselves, this painting instead seeks to provide a look past the curtain into the way we excavate burials. Because our burial excavations are obscured from public view, it may be difficult for visitors to get a good sense of what goes on inside. This painting provides a window into our process, along with all of the preparation work and tools we use to get it done.

The results of this process were three illustrations which convey different types of detailed information for viewers who are interested in our burial excavations, but who may not want or need to look at photographs of the remains. The process of illustrating these burials benefits not only the public, but the artist — as a newer member of the team, illustrating these burials has allowed me the closest possible study of these remains without personally excavating them. To draw something, to faithfully reproduce it, is to know it. Through illustrating these three burials, not only do I know them better, but more visitors are able to become familiar with our burials and how we excavate them. Even so, these illustrations represent only a small portion of the work that went into our burial excavations this year.

For more information regarding the construction of our burial structure, the methodology behind our excavations, and the forensic analysis and conclusions drawn from each of these burials, explore our Dig Updates from August, September, and October 2024, as well as our Dig Deeper video series on YouTube.

(L) The final watercolor illustration depicting burials JR1237, JR1847, and JR1335 in situ (M) The final pen and ink drawing depicting burials JR1237, JR1847, and JR1335 in situ (R) The final painted working scene, depicting Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley excavating burial JR1237 within the burial structure.