Archaeologists are conducting ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys just south of the Jamestown Rediscovery Center prior to the installation of the Ellen Kelso Memorial Garden. They hope that they might discover structures related to the 1660s statehouse nearby. Work is concluding on the “burial” site near the Pitch and Tar Swamp as well as the north Church Tower and 1607 burial ground excavations. The conservation team is excited to receive a new X-ray detector, an addition that will greatly aid their conservation efforts. In the Vault, curators and archaeologists are hard at work on the reference collection, going through the artifact archive to organize, analyze, and process artifacts for the effort. Among the artifacts processed this month are hones or whetstones, tobacco pipe waste, mysterious clay balls, and gun flints.

In preparation for planting the Ellen Kelso Memorial Garden, the old plants were removed, leaving a bare surface perfect for ground-penetrating radar (GPR). The archaeological team took advantage of the opportunity by making two GPR surveys of the area, one at 350 MHz, the other at 900 MHz. The 350 MHz scan goes deeper into the soil but provides less resolution while the 900 MHz signal can’t penetrate as deeply but gives higher resolution images. By surveying the same area at both frequencies, the archaeologists will be able to compare and contrast the different results and hopefully discern any possible features that require trowel-in-ground investigation. The garden sits on the same ridge as the 1660s statehouse and so could possibly contain features related to that building. The area in front of the Archaearium is also slated for GPR surveying; an earlier survey suggested a building may have existed there and the team wants to corroborate those results prior to conducting excavations.

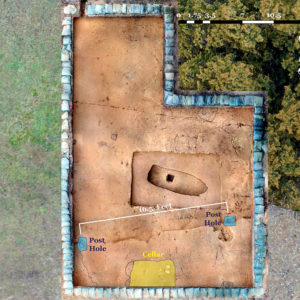

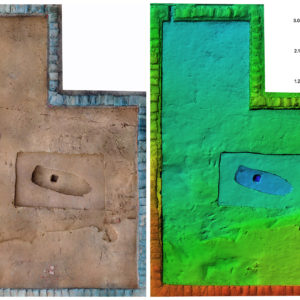

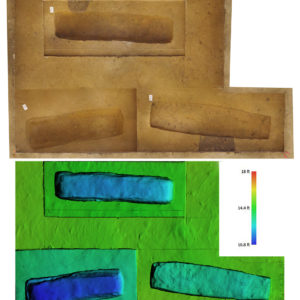

The team is currently backfilling the “burial” site near the Pitch and Tar Swamp. Though there were no discernible human remains found in the grave-like feature, there were several postholes, including two that were 16 ½ feet apart. This distance is called a “pole,” a common unit of length in surveying in the 17th century, so these postholes could have been part of a larger fence line. Future excavations of adjacent squares will be necessary to better understand what these postholes relate to. The most interesting find in these excavations was a cellar, 6 feet wide and at least 3 feet long; its full length extends beyond the current excavation area. GPR data suggests it is approximately 3 feet deep and houses objects within it. The archaeologists can’t yet date the cellar but hopefully a review of the artifacts and analysis of other nearby features will shed light on when and how it was used.

At the north Church Tower excavations a GPR survey of the fort’s eastern palisade wall here is the final task before work is complete. Once the palisade has been imaged with GPR, the area will be backfilled. Afterward, the team will analyze the features and artifacts found here to determine exactly how this space was used through time.

Inside the 1607 burial ground, all of the soil in the easternmost burial excavated in October will be “floated” to search for macrobotanicals. Flotation is a process by which objects of different densities are separated by placing them into a specialized water tank (Watch a video describing this process). Samples from the other two burials will also be floated as will a control sample from the excavation square’s walls. In addition to the flotation, samples of soil from different areas of the burials were taken. Soil was extracted from the area where the lungs would have been and similarly where the stomach, and the colon would have been. These samples will be tested for the presence of pollen and phytoliths, both things that can give us hints about what the colonists were eating and what the environment was like in the summer of 1607 when these men perished.

In the Vault, the curatorial team is formulating a responsible research plan for the human remains excavated in October. The curators will be working with outside experts to conduct isotopic testing on samples of teeth and bones. The isotopes contained there can tell us much about where these people grew up, where they lived in their later years, and what they ate.

Next door in the lab, the new X-ray detector has been installed. Cam Ward of Pinnacle X-ray Solutions arrived for two days of setup and training with the conservation staff. Several trays of artifacts were X-rayed while Mr. Ward was on site to give everyone hands-on experience and iron out any issues before his time with the team was over. Jamestown has been without a functional X-ray machine for several months and this will be an important tool for the conservators as they strive to preserve and protect the objects found in the field.

Curatorial Intern Lindsay Bliss has completed her internship and was invaluable in her efforts finding faunal remains in the fort’s second well. The third-party zooarchaeologists conducting the formal analysis of the remains will release their report in January. We plan to undertake the same process for the fort’s first well in the future, including a formal analysis/identification of faunal and botanical remains by an outside group of experts. The first well didn’t have as many botanical remains as the second, but had more faunal remains, including over 300,000 animal bones. Interestingly, the well was open during the Starving Time winter of 1609/1610 so the well contained the butchered remains of animals not normally eaten by the English.

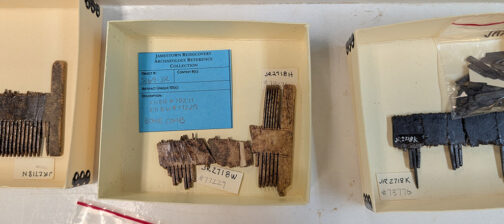

When it was too cold for the archaeologists to work outdoors, they have come inside to help the curators with their work. The curatorial team’s effort to build a reference collection — a single representative artifact selected from each type found at Jamestown to aid in future identification and research — is guiding much of the efforts here. Archaeologists have been working in the Vault’s archive on the second floor gathering all known examples of several different types of artifacts missing from the reference collection so that the curators can compare and select an artifact that best represents the type. Additionally the team is weighing and measuring any artifacts that are missing this data in the collections database.

One of the types being collected and analyzed are hones or whetstones — stones used to sharpen knives and other bladed tools. Most of these are sandstone but there are examples made from other stone types as well. Some are heavily worn by the sharpening process but it is unknown whether these were used for stone or metal sharpening. Perhaps microscopic analysis could help determine this. Another artifact type being consolidated and organized for the reference collection is tobacco pipe waste. These fired ceramic pieces of tobacco pipes are numerous in the Jamestown collection, some of which even bear fingerprints, perhaps of Robert Cotton, Jamestown’s first pipe maker. Also added to the reference collection this month are clay balls — smooth, rounded, and fired. The curatorial team is unsure what these were used for but they show up in contexts as early as 1608. Maybe these were heated and used for cooking. Maybe they were the specific amount of clay used to create pipes. Maybe they were used for games such as bowling. Maybe somebody was just bored.

Gun flints are another artifact type being pulled and analyzed for the reference collection. There are over 100 of these in our collection, and like the other artifacts being pulled for the reference collection, they’re being weighed and measured to update the collections database. Each one is also being examined to confirm it’s truly flint, an indication that it’s of English rather than Virginian origin. Finally, Jamestown’s shell collection is also receiving the reference collection treatment. Many initial database identifications list them simply as “snail,” so research is ongoing to more precisely identify the species and thus perhaps where they came from. These efforts have led to the discovery of several newly-identified types as well as more examples of common types such as the ribbed mussel, used to create shell beads inside James Fort.

related images

- The “burial” site showing the cellar and postholes location

- An orthomosaic and digital elevation model (DEM) of the “burial” excavation near the Pitch and Tar Swamp.

- Finishing up archaeology at the “burial” site near the Pitch and Tar Swamp.

- The “burial” excavations near the Pitch and Tar Swamp after being backfilled

- The north Church Tower excavations aren’t yet backfilled.

- Archaeologists carefully dismantle the burial structure at the 1607 burial ground. They will use it again in later excavations.

- A heavily-used hone (whetstone)

- A hone (whetstone)

- Tobacco waste fragments

- Gun flints in the Jamestown Rediscovery Collection

- Ribbed Mussel. This type of shell was used to make beads inside James Fort.