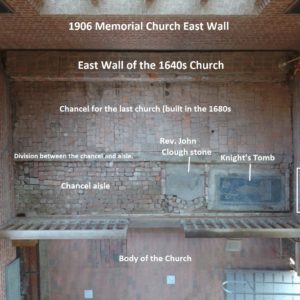

During April, the Jamestown Rediscovery team continued excavations in the 1907 Memorial Church, site of three historic Jamestown churches. They focused on the Knight’s Tombstone and chancel floors related to all three churches built on the site. Each investigation led to exciting discoveries and new questions.

The month began with preparations for the Knight’s Tombstone conservation. Discovered during excavations by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) in 1901, this ledger stone with the outline of a knight was found lying just inside the south entrance for the church. The team speculated it was moved to the chancel aisle of the late 17th-century church, and was turned to a north-south orientation to be used as a paver for the entry way. It is believed that the original interment would have been oriented east-west, consistent with 17th-century burial practices. Excavations around the knight’s tombstone revealed that preservationists placed the stone on a base of brick and concrete in 1905 during the construction of the Memorial Church. They also repaired the fractured pieces of the stone at that time.

Prior to the tombstone’s removal, archaeologists examined a recently exposed portion of tile floor thought to relate to the 1640s church’s chancel. Concerned that moving the stone could potentially damage the exposed floor section, the team decided to excavate some of the surviving tiles and mortar. Although the decision was difficult, the prospect of finding an earlier floor made it easier.

“In 1902, when the APVA preservationists were digging burials in the chancel, they excavated right up next to this tile floor. Most of the tiles hung on the edge of the profile, and many were heavily fractured. Another consideration about whether or not to excavate some of the tiles was that we could see evidence in the profile of possibly another floor beneath this 1640s tile and mortar,” explained field supervisor Mary Anna Hartley.

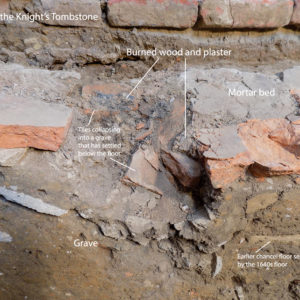

Apparently the early excavators removed the debris above the tile floor, and then left the exposed tiles in place. Fortuitously, two tiles had collapsed a few inches into the top of a settled grave, creating a crevice into which some of the original soil sealing the tiles survived. Containing burned wood and charred pieces of plaster, the layer is characteristic of rubble from a burned building and is possibly related to Bacon’s Rebellion. In September 1676, Nathaniel Bacon led a rebellion over Indian policy and colonial rule during which much of Jamestown including the statehouse and the church was burned. The presence of this burned layer offers evidence that the floor it seals relates to the 1640s church set aflame.

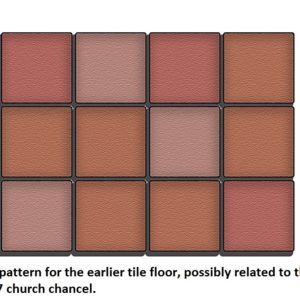

Removal of some of the 1640s tiles revealed the mortar bed of an earlier tile floor. While no tiles survived in the mortar, impressions and joint lines did, which indicated their size and the tile pattern. While the 1640s tiles were laid like brickwork, offset from each other, the tiles in the earlier floor were laid in a grid pattern side by side. Could this earlier floor relate to the 1617 church? It is decidedly possible!

Following investigation of the chancel floors, the team shored up the profile wall and covered the area with sandbags to protect it during the knight’s tombstone removal. Rediscovery is working on the conservation of the tombstone with Jonathan Appell, a renowned monuments conservator based in Connecticut. Appell began his work by using a diamond blade saw to remove the Portland cement skirt, which surrounded the tombstone’s edges. Once the stone was freed from the cement skirt, he used wooden wedges to gently pry the stone pieces up from the base. Fortunately, instead of embedding the stone entirely in concrete, early preservationists used a bed of soft shell mortar. This was the first of many discoveries about how well the stone repairs were handled by early APVA preservationists.

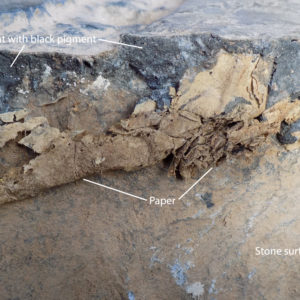

Appell anticipated that the broken pieces were completely cemented together during the 1905 conservation. Nevertheless, he was optimistic that the repairs would come apart easily, thereby allowing him to remove each piece so he could strip off the Portland cement that held them together. The circumstances proved better than expected! Wet Portland cement was applied only along the top edges of the cracks, and the individual pieces separated exactly where they should. Because they were set in shell mortar, Appell was able to lift each section of stone without damaging them. As the sections were removed, the team discovered remnants of paper, yellowed from age, which had been placed along the interior surfaces to prevent concrete from dripping into the cracks as it was applied. It was the best case scenario!

Current research suggests that the Knight’s tombstone originally marked the grave of Sir George Yeardley, who died in 1627. Knighted and appointed governor of the colony in 1618, Yeardley presided over the first General Assembly that met in 1619 in the 1617 church “quire” [choir]. The stone would have been imported to the colony from England. Appell noted that it was remarkable to have a stone ornamented with such a large quantity of brass. In his line of work, he sees many historical tombstones with surviving slate inlays because they are far less likely to be robbed than metal. “This must have been an impressive ledger stone with its original brasses,” Appell commented. “It’s a very high end piece.”

For more information on how the conservators moved the Knight’s Tombstone, check out the video update!

related images

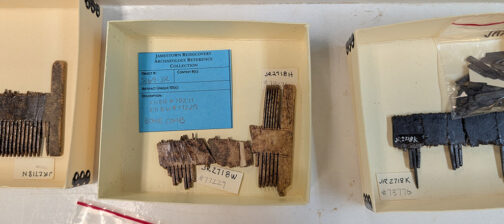

- Features of Jamestown’s many churches

- These fragmented tiles were uncovered by the early 20th century excavators but were not removed as in other areas. Archaeologists believe that this is a portion of Jamestown’s fourth church completed in 1647. At least four tiles were sealed by burned wood and plaster likely related to when the church burned in 1676 during Bacon’s Rebellion. Because of the plans to move the Knight’s Tombstone and the possibility of uncovering an earlier chancel floor below it, a few fragile tiles were removed. The team did find a mortar bed for another chancel floor beneath this one.

- Tiles and mortar of the 1640s church

- Archaeologists believe that this section of the 1640s church chancel floor collapsed into a grave as it settled. This is likely why any evidence of burning from the 1676 fire survives.

- Mary Anna Hartley excavates a section of surviving chancel floor in preparation for the removal of the Knight’s Tombstone (on right). Evidence suggests that this floor relates to the 1640s brick church. The burned wood and plaster found resting directly on some of the tiles relates to the fire that burned that church during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676.

- Tile pattern for the 1640s church chancel floor.

- Tile pattern for the earlier tile floor, possibly related to the 1617 church chancel.

- Carved areas for missing brass inlays on the Knight’s Tombstone

- Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell saws away the Portland cement skirt bordering the Knight’s Tombstone in preparation for the stone’s removal

- Jamestown Rediscovery conservators Michael Lavin and Dan Gamble discuss the removal of the concrete skirt from around the edges of the tombstone with Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell

- Remnants of paper were stuffed in between the broken pieces of the Knight’s Tombstone in order to keep the watery cement mixture used along the top edges from dripping and coating the entire surface

- Appell remarked that it was fortunate that the APVA preservationists did not embed the entire stone in Portland cement. That was often done in the early 20th century to the detriment of the stone.

- Jonathan Appell and Michael Lavin moving the Knight’s Tombstone up on top of the cart. Over the next few weeks, the stone will be cleaned in preparation to be mended back together.

- Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell leads the Rediscovery team in moving the largest intact piece of the Knight’s Tombstone onto the cart where it will undergo conservation during the next few months.

- JR Conservator Michael Lavin and Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell arrange the fragments of the Knight’s Tombstone on the cart

- Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley removes the shell mortar and slate shims on top of which the Knights Tombstone sat. The bricks are part of the base built in 1905 to hold the stone.

- In order to protect the exposed portions of chancel floor, the team built a thick sandbag wall up against the profile wall. The precaution proved successful in preserving the archaeological features during the removal of the tombstone.

- JR Conservator Dan Gamble carefully brushes away remnants of Portland cement used to mend the broken pieces of the Knight’s Tombstone together during the early 20th century.