Records of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA, now Preservation Virginia) indicate that over the centuries, the remains of the 17th-century brick Jamestown church and churchyard suffered greatly from vandalism by people who removed items from the historic site. The souvenirs of choice were bricks from the church or fragments of the tombstones. During expositions to see the ruins, the APVA hired as many as 10 men to keep visitors from stealing bricks! Mary Jeffery Galt remarked that when the organization acquired the property, several of the graves had been dug into, suggesting they had been robbed.

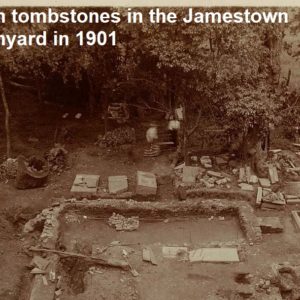

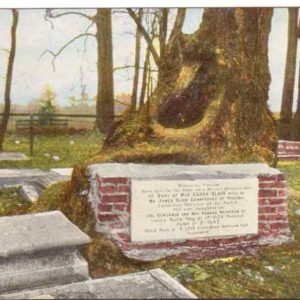

Early images of the churchyard show broken tombstones and monuments scattered about the yard and in between trees and bushes. The vandalism was so pervasive in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, the previous property owner, Mr. Edward Barney, removed many of the stones and took them to his house on the Island for safekeeping. He “charted” and “staked” their original placement in the churchyard. However, when Galt and other ladies of the APVA’s Jamestown Committee sought to return the stones to their rightful places, the chart and stakes marking the graves had been lost. Unfortunately, the ladies could only guess the original locations of the stones. They relied partly on previous records of inscriptions from the mid-19th century and also on their excavations of some of the graves to inform their placement. The Committee hired stone masons from Richmond, including William Leal, to cement the stone fragments together in order to prevent further thief of the fragments. They also hired masons to repair and enhance the crumbling circa 1800 Ambler-Lee churchyard wall.

Since the restorations of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, there had been very few improvements to the either the Jamestown cemetery or the churchyard wall. Years of neglect had taken its toll on the work, considered inferior by today’s standards of conservation and restoration. In fact, the early masons had arbitrarily and haphazardly cemented tombstone fragments together. Thus, both projects were added to the list of improvements ahead of the commemorations of the 400th Anniversary of the first General Assembly. With the facelift of the 1907 Memorial Church, and because of the upcoming public programming that will be held in the church, the work was deemed crucial.

Rediscovery conservators consulted and contracted with Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell, who had previously worked with the team to conserve and restore the Knight’s Tombstone. Appell and his team assessed ways to repair the churchyard stones and portions of the crumbling churchyard wall. Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin explained, “One of our major challenges was how to interpret the churchyard so that it respected the early preservation efforts made over 100 years ago, but also to take the opportunity to correct the faults where we could.”

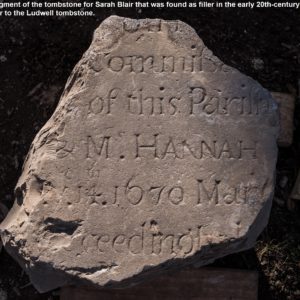

During the winter, Appell spent weeks carefully deconstructing the masonry wall and repairing the tombstones. In one instance, he discovered part of a tombstone inscribed with the date 1670, which a mason had turned upside down and used as filler in a gap of Phillip Ludwell’s tombstone. The rediscovered piece matched a stone fragment for Sarah Harrison Blair found in another area of the yard. Appell, who has worked across the United States on gravestones and monuments of all periods, said he has never seen “anything in such a diminished condition and with so many loose original stones” as he has in the Jamestown cemetery.

Also in February, Director of Archaeology Dave Givens and Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley followed up with Mr. Purcell Bailey to conduct a more extensive interview about his time with the Civil Conservation Corps (CCC) in Williamsburg. Enrollees who worked with Bailey, excavated at the Angela Site and other sites across Jamestown Island with the National Park Service in the 1930s. Jamestown Rediscovery Fellow Chardé Reid (a PhD student at the College of William & Mary) accompanied Givens and Hartley on their trip across the James River to Bailey’s home in Surry County, Virginia, to assist with the interview.

As the Rediscovery team filmed over three hours of conversation with Bailey, he talked about some of the men he worked with at the camp and camp life. He also spoke of his service with the U.S. Army during World War II and his experience at Utah Beach during the D-Day. Bailey described his life before the CCC as “terrible” and remarked that the experience really opened up the world for him. Reid showed Bailey some photographs of the CCC camp, causing him to remember how his talent for painting rooms had helped the camp receive a first class award on one occasion. Bailey, who served as Assistant Educational Advisor, said he played baseball with some of the men who excavated at Jamestown. He recalled how his team did so well that they made it to the championship held in Gettysburg; they did not win, but at least they got a trip to Pennsylvania!

This month’s YouTube update is a time-lapse showing the discovery of the 1617 church’s west foundation inside the old church tower.

related images

- Broken tombstones in the Jamestown churchyard in 1901

- The Jamestown Churchyard during Mary Jeffrey Galt’s 1901 church excavations. Note the stones spread around the yard and the crumbling brick wall in the background, built by the Ambler and Lee family around 1800. In the foreground are the east wall of the brick church and the Knight’s Tombstone prior to restoration.

- A postcard showing the previous restoration work

- Jonathan Appell and Director of Conservation and Collections Michael Lavin discuss the best course of action in the Jamestown cemetery. Many of the stones were in great need of repair.

- Monuments conservator Jonathan Appell moving one of the modern stone markers in the Jamestown churchyard

- Tombstones next to the east end of the 1907 Memorial Church during the cemetery restoration this winter

- Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell works on the Jamestown Churchyard Project

- Jonathan Appell examines the fragments for Phillip Ludwell’s tombstone after disassembling the repair work done in 1901. Many of the stones in teh lower end were unrelated to Ludwell’s original.

- A fragment of the tombstone for Sarah Blair that was found as filler in the early 20th-century repair to the Ludwell tombstone

- Dave Givens examines a monument fragment found upside-down in one of the APVA-repaired tombstones

- In addition to repairing the tombstones, Appell and his team also improved portions of the brick churchyard wall that were enhanced in the 19th century

- Appell and his team repairing the previous brickwork that was laid in the 19th century over the churchyard wall

- Bailey looks at some images from the CCC camp in Williamsburg

- Jamestown Rediscovery with Mr. Bailey following their interview with him about his time with the CCC in Williamsburg