This summer eight different 10-by-10 foot units will be opened just south of the 1907 Memorial Church. In June the 2012 Field School students began screening dirt from those squares.

Alexi Garrett lucked out right away: a 1685 silver Spanish coin made in Lima, Peru, and marked with the assayer’s initial: R.

“It was my very first bucket of dirt on my very first day out here,” said Garrett, who just graduated with an English and History double major from St. Olaf College in Minnesota. “The joke is that for me it’s all downhill from here.”

This is not the first Spanish coin found in the James Fort site from that period, but this one seems to have a high silver content. This coin is not milled on the edges or perfectly circular. It is called a “cob coin” because it was cut from the end of a rounded bar of silver and then weighed to determine its value—which in this case is 1 real. “Cob” is an English word that derives from the Spanish word cabo, which means rope, but also a bit or a piece, or the end.

The coin came from the landscaping fill in a unit opened just south of the 17th-century tower at the west end of the 1907 Memorial Church. Nearby another Spanish coin was found in mid-June: This copper coin was made in Segovia, Spain, in 1601 and features the image of the Roman aqueduct that still stands in that city.

Why are Spanish coins in an English settlement? The Virginia Company had the authority to mint coinage for its colony but never did. It was too expensive to make money that was worth its weight in a precious metal.

“It was a dynamic time,” Staff Archaeologist David Givens said. “You wonder why the Virginia Company sent 104 men here and not a thousand. They just didn’t have the money or the ships to do it. The Spanish had the ships.”

Some pocket change, especially foreign coins, did circulate, enabling colonists to purchase commodities from individual sailors on visiting supply ships that were part of the transatlantic economy. A silver coin cut into halves or quarters could still literally be worth half or a quarter of its whole value. Coinage remained scarce in Virginia throughout the colonial period.

The units south of the Memorial Church have produced more than coinage. Archaeologists have found a St. Albans projectile point made of a striped stone called felcite from the Nottaway River basin on the North Carolina border. The point is probably 8,000 years old (the Early Archaic period), has serrated edges, and its tip is broken off.

Unfortunately, there is no soil context to give further evidence about the recently-discovered coins or the St. Albans point or a broken English key or even a cannonball from a light cannon known as a falconet. “This fill has been moved several times. Who knows where it came from originally,” Jamestown Rediscovery Staff Archaeologist Danny Schmidt said.

Givens said that what is found in the units to the south of the church tower may answer the lingering question of how old the tower is. Estimates about its construction date have ranged from the 1640s to the 1690s.

The other focus of the 19th archaeological season at Historic Jamestowne is an L-shaped cellar at least 25 feet long from the early James Fort period (1607-1610). This feature is in an area west of the brick church tower and north of the recently rediscovered 1608 church. This cellar aligns with James Fort’s first well, which sits just 10 feet away to the west and at the same angle.

There is hope that if this does turn out to be a well, it can solve the mystery of the location of a third James Fort well apparently dug in 1611.

“Consequently, any artifacts from it can be tightly dated and could determine how the new martial laws instituted by Lord De La Warr affected the material lives of the colonists,” said Dr. William Kelso, Director of Archaeological Research at Historic Jamestowne. “After they were abandoned, the Fort wells have typically produced a trove of artifacts.”

Recently the cellar has produced a turtle shell, a horse jawbone, and the medallion of a German stoneware jug in redeposited subsoil, taken from somewhere else near the fort. The jug medallion fits with sherds from the neck of the jug found in the cellar/well just 10 feet away.

“I think this is just the tip of the iceberg. It looks like we’ll see a lot of cross-mends between what we are finding now and the pieces we found in the well/cellar,” Schmidt said.

Senior Archaeological Curator Bly Straube said this linkage between pieces relates to the clean-up of James Fort in June 1610 ordered by the newly-arrived Lord Governor and Captain General of Virginia, Lord De La Warr. She has overseen the mending of thousands of artifacts.

“That’s a process I am constantly doing across the whole site. That’s why I have all those pieces out on the tables in the lab, to make those connections and to show the links between the features on the site,” Straube said.

The cellar being examined this summer has also produced the base of a candlestick that is rare for its material: pewter. The Jamestown Rediscovery collection has brass and ceramic candlesticks, but few aged pewter objects survive contact with the air.

The cellar being examined this summer has also produced the base of a candlestick that is rare for its material: pewter. The Jamestown Rediscovery collection has brass and ceramic candlesticks, but few aged pewter objects survive contact with the air.

Senior Conservator Michael Lavin said, “Pewter is in the tin family. It’s more tin than lead. Pewter does not survive in clay/acidic soil because the tin deteriorates in the ground.”

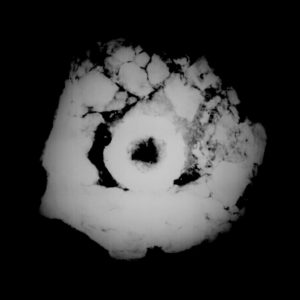

A decade ago the archaeologists found a pewter spoon in a man’s pocket in a burial, but the spoon’s shape quickly flaked apart. One way to get information before such disintegration is to keep the object within dirt until it can be pictured with an x-ray. This procedure showed the pewter candlestick to be about five inches across.

The Jamestown Rediscovery team did the same for a sword’s basket hilt found in the L-shaped cellar. Now that an x-ray has shown the outline of the hilt, the next step is air abrasion to clean the hilt of the dirt, and that will take a long time, Lavin said.

“We have other basket hilts in our collection. We won’t know if this is unique until we conserve it,” he said. “We have only one that is a whole sword. [The settlers] were dismantling them on purpose. There is valuable steel in the blade.”

related images

- The 2012 Jamestown Rediscovery and UVA Summer Field School at Historic Jamestown Excavating Near the 17th-Century Jamestown Church Tower

- The Pewter Candlestick Base as It Appeared Before Being Removed to the Lab for Conservation.

- An X-Ray of the Base of a Pewter Candlestick Found in an Early Cellar

- An Archaic Projectile Point Found Near the Church Tower

- A 1689 Spanish Reale, from Silver Mined in Peru, Found Near the Church Tower